3.4 Clausius-Clapeyron

Boiling Water at Different Pressures¶

By convention, we define the melting point and boiling point of water as 0°C and 100°C, respectively. However, in reality, these temperatures depend on pressure.

For example, a pressure cooker raises the boiling point above 100°C, allowing food to cook faster. In igh-altitude cities like Denver, where atmospheric pressure is lower than at sea level, water boils at temperatures below 100°C, requiring adjustments to cooking times. Conversely, in a vacuum, water boils at room temperature or lower.

These observations show that the boiling point of water is not fixed, but rather a function of pressure. This dependence follows from Gibbs’ phase rule, which determines how many independent variables (such as temperature and pressure) must be specified to define a system at equilibrium.

Gibbs’ Phase Rule¶

Degrees of Freedom in a System¶

Consider a system where water is not undergoing a phase transition. If we specify the temperature, the pressure can still vary independently, and vice versa. However, during boiling, where liquid and vapor coexist, pressure and temperature are linked; changing one determines the other.

This difference in behavior arises because each phase transition removes a degree of freedom from the system. A degree of freedom refers to how many independent variables must be specified to fully define the state of the system.

To formalize this, we revisit Equation (1.1.23), the ideal gas law:

This equation has four variables: pressure , volume , temperature , and number of moles (with being a constant). If we fix , there are three variables and one equation, meaning we have two degrees of freedom. We must specify two values (e.g., and ) to determine the third (). This general principle extends to all thermodynamic systems.

For pure liquid water, we have a single chemical component () and one phase present (). Applying Gibbs’ phase rule:

This means there are two degrees of freedom, so temperature and pressure can vary independently.

However, during boiling where liquid and vapor coexist, we have two phases present (), and therefore:

This means temperature and pressure are no longer independent—fixing one determines the other. The mathematical relationship between them is given by the Clausius-Clapeyron relation, which we will derive in the next section.

Phase Equilibrium Conditions¶

At equilibrium, a system undergoing a phase transition must satisfy three conditions:

- Thermal equilibrium: The temperature of the coexisting phases must be equal.

- Mechanical equilibrium: The pressure of the two phases must be equal.

- Chemical equilibrium: The chemical potential of the two phases must be equal.

These conditions ensure that, at equilibrium, the rates of mass, heat, and energy transfer between the phases are balanced, so the system remains in a steady state

Gibbs’ Phase Rule Implications¶

The consequence of Gibbs’ phase rule is that in a single-phase system, pressure and temperature can vary independently. However, during oiling, the system has only one degree of freedom. This explains why:

- At a fixed pressure the boiling temperature is uniquely determined.

- At a fixed temperature, the boiling pressure is uniquely determined.

For example:

- At sea level ( atm), water boils at 100°C.

- In Denver ( atm), water boils at <100°C.

- In a pressure cooker ( atm), water boils at >100°C.

- In space ( atm), water boils at room temperature or lower.

The relationship between temperature and pressure during boiling is described by the Clausius-Clapeyron equation, which we derive next.

Equilibrium of Liquid and Gas¶

The boiling point of water is often stated as 100°C, but as we saw above, it depends on pressure. Similarly, the boiling pressure of water will also depend on the temperature. To understand why, we analyze the equilibrium condition during a phase transition:

By definition, we have and , the temperature and pressure of the system at the boiling point. For both phases, we write the Gibbs free energy as:

From the integral forms of internal energy and Gibbs Free energy given by Equations (2.2.4) and (2.3.17), we can derive

Applying the product rule gives

Combining these expressions with Equation (3.4.9) yields

Dividing by the number of mols of liquid and gas gives us the derivative of the chemical potentials as a function of specific entropy and volume:

The boiling point occurs when the two phases are in equilibrium, so the chemical potentials of liquid and gas phases are equal (). Thus we can set the expressions in Equation (3.4.13) equal to each other:

Rearranging this expression, we can write

To simplify this expression, we define the latent heat of boiling to be

where is the heat exchanged during boiling and is the number of mols of the boiled substance. The latent heat of boiling has been measured for many materials, including water.

Recall Equation (1.3.7), which states that for a reversible process the heat flow will be equal to the temperature multiplied by the change in entropy . We can now simplify Equation (3.4.15):

The molar volume of water vapor is approximately 30 L / mol (at 100°C and 1 atm), which is much higher than the molar volume of liquid water which is approximately 0.018 L / mol. We can therefore make the approximation , giving a simpler Clausius-Clapeyron Relation for water:

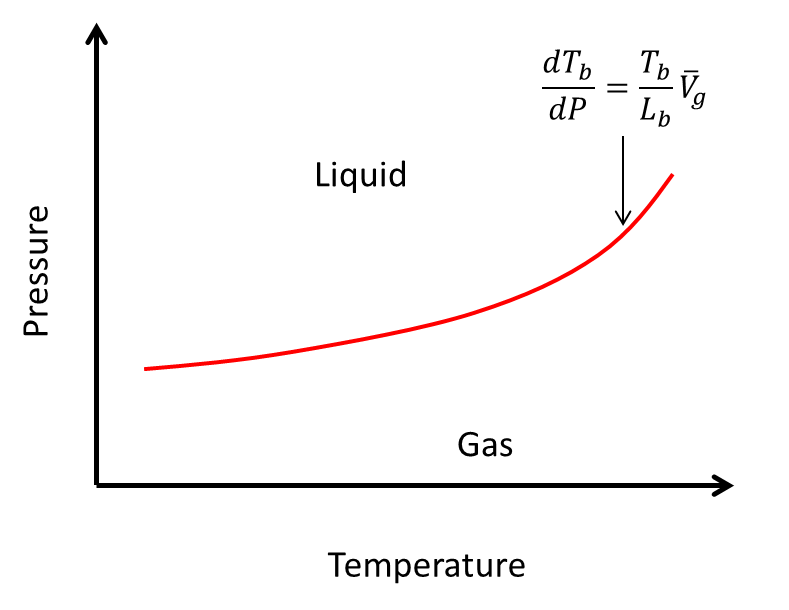

This expression is plotted for water in Figure 3.4.1. Above the red line, the liquid phase is stable. Below the red line, the gas phase is stable. Along the red line, both phases coexist.

Figure 3.4.1:The approximate Clausius-Clapeyron relationship for water, given by Equation (3.4.19).