The Problem

Overview¶

Human civilization emits millions of tons of CO₂ into Earth’s atmosphere every year. Natural processes which reduce atmospheric CO2 concentration include:

- Dissolution in sea water.

- Incorporation into the terrestrial biosphere, especially forests and grasslands.

- Weathering of silicate rocks.

- Accumulation of organic material under anaerobic conditions such as in wetlands or peat bogs.

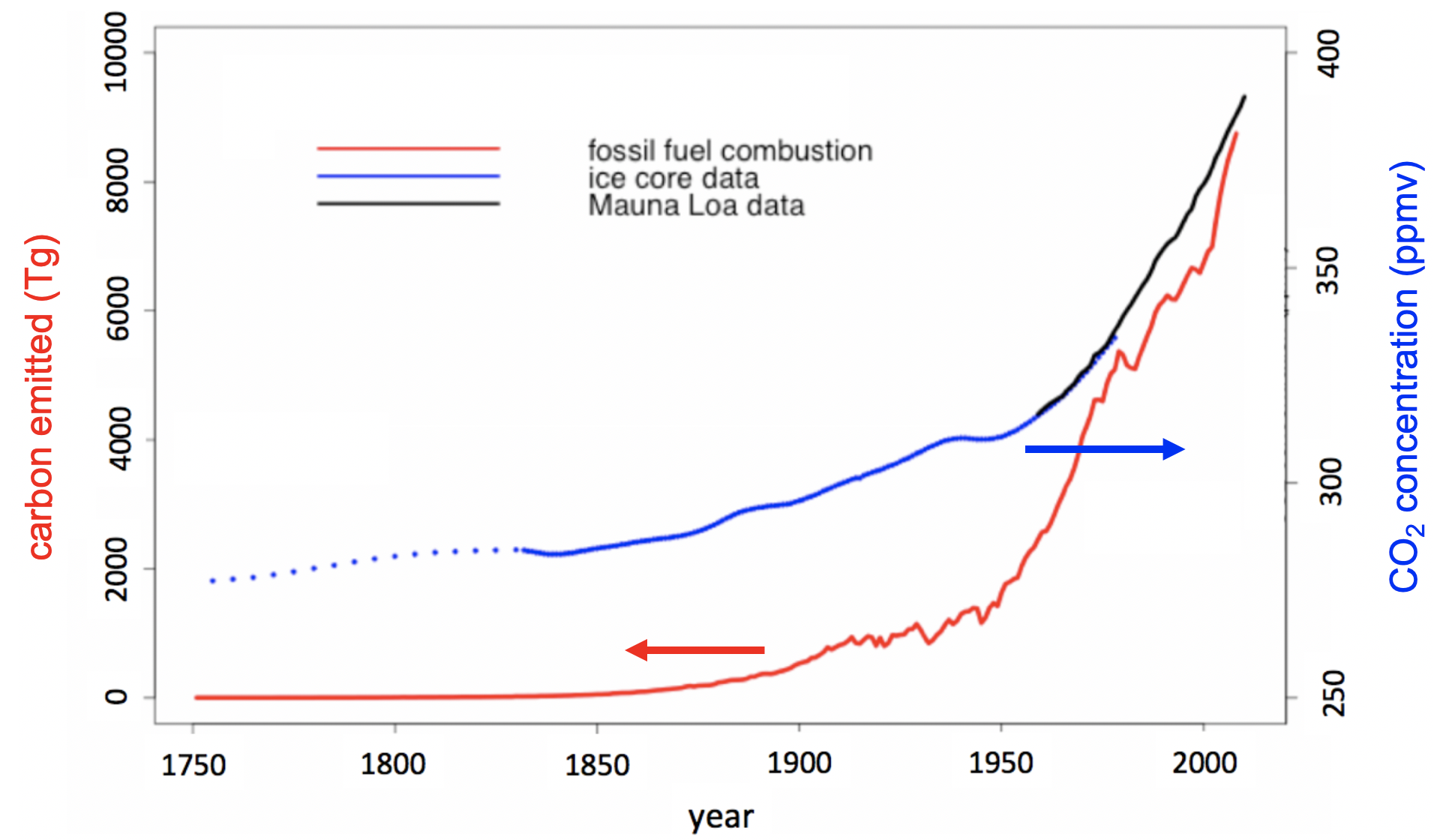

Unfortunately, these natural processes cannot keep pace with the CO₂ released by human industrial, transportation, and agricultural production. The net result has been a consistent rise in atmospheric CO₂ concentration over the past few hundred years, shown in Figure 1.1.1.

Figure 1.1.1:Atmospheric concentration of CO₂ (Tg) compared to CO2 produced by human civilization (ppmv). Adapted and used with permission from ML Machala, Carbon-Neutral Synthetic Fuel.

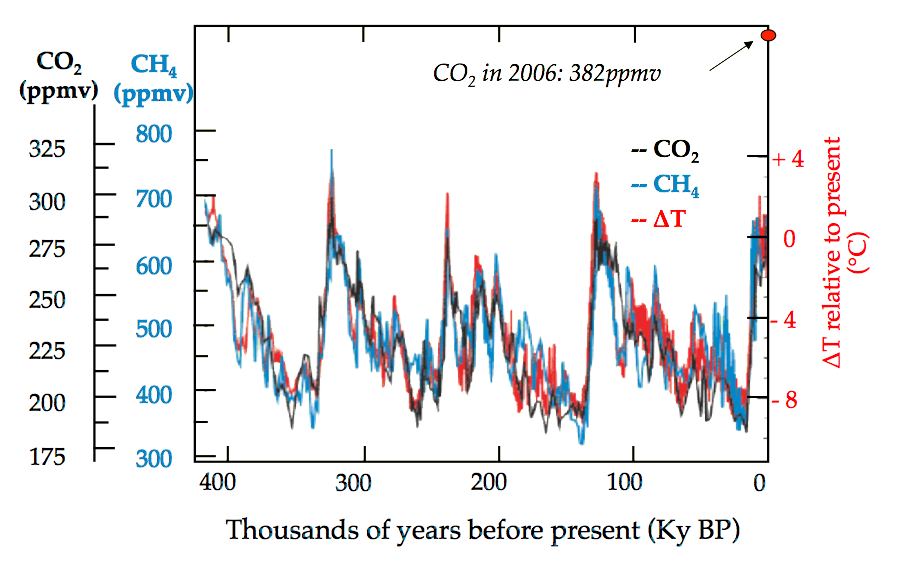

Figure 1.1.2 demonstrates the atmospheric CO₂ is very highly correlated to the global mean temperature. Historically, CO₂ concentration has not risen above ~325 ppmv, but in May 2023 it rose to 424 ppmv (NOAA Global Monitoring Lab). This recent rise or CO₂ concentration over the past ~200 years is extremely rapid compared to the geological timescales of previous CO₂ oscillations.

Figure 1.1.2:Correlations between concentration of CO₂, CH₄, and temperature. Courtesy of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2001), Oreskes (2004), Stainforth et al. (2005).

The scientific consensus is that increased greenhouse gas emissions (primarily CO₂) is driving anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change (Scientific consensus on climate change). To tackle this issue, many researchers have proposed various methods of CO₂ capture and sequestration, either directly from the atmosphere or from industrial or agricultural processes before the CO₂ is released into the atmosphere. For example, we could capture CO₂ from a flue, which is a pipe or channel that transports exhaust gases from industrial processes, such as power plants, cement production, or steel manufacturing. This captured CO₂ could then be compressed, transported, and stored underground in geological formations, or utilized in processes like enhanced oil recovery or the production of synthetic fuels and materials.

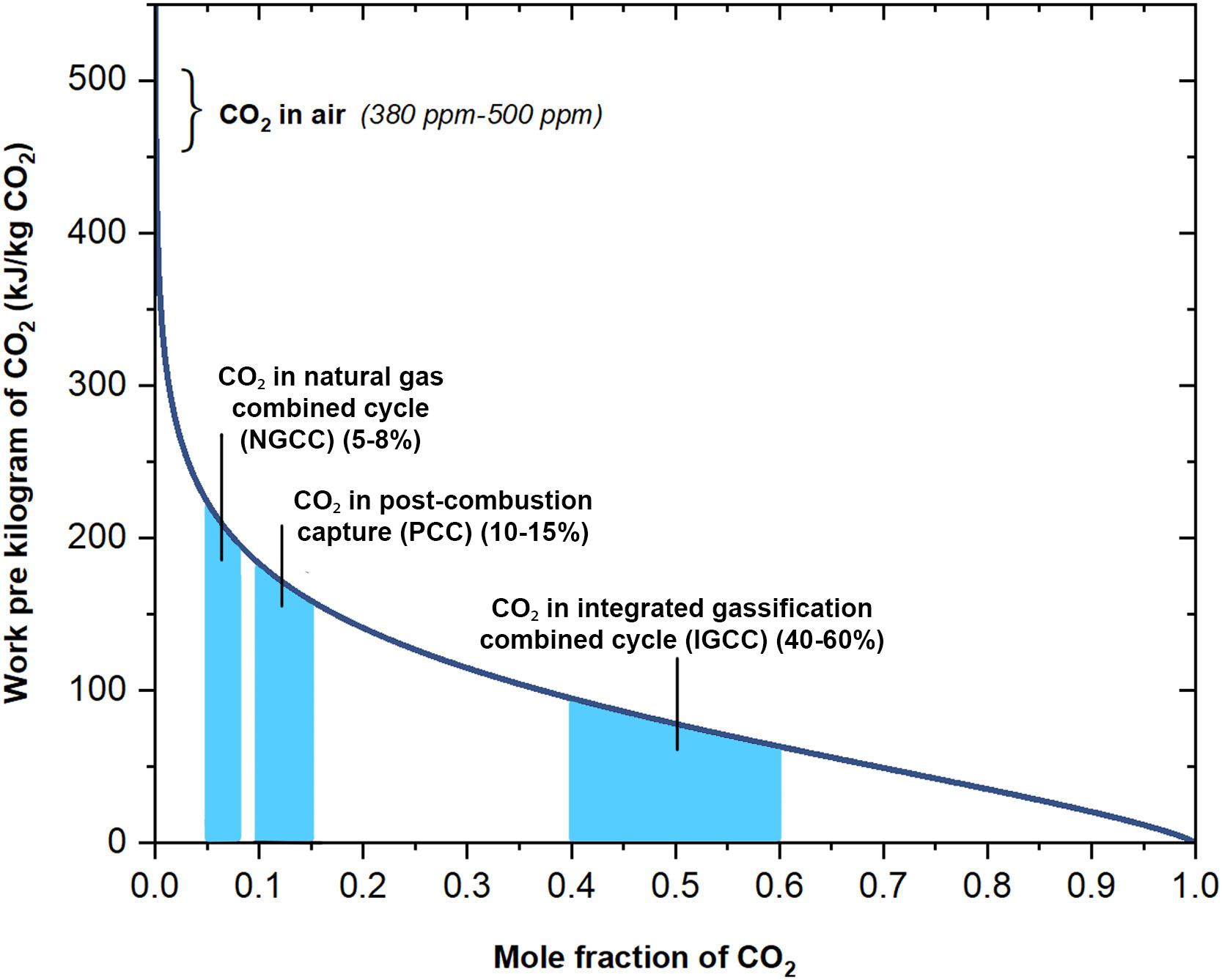

Comparing CO₂ capture from the atmosphere or a flue, which process is more economical? Typically the more economical process is the one which requires less energy. Figure 1.1.3 shows the relationship between the energy required to extract CO₂ from a gas mixture as a function of the CO₂ concentration.

Figure 1.1.3:The dependence of the thermodynamic minimum energy to capture CO₂ from a gas mixture (kJ/kg CO₂) at 298 K on the initial CO₂ molar concentration. Adapted from Zhang et al. (2023).

There is a large energy difference between extracting CO₂ from the atmosphere versus extracting it from common flue gas concentrations, including NGCC, PCC, and IGCC. The energy difference is also somewhat large between these different power plants. In this chapter, we will learn how to construct this type of graph and thereby evaluate the thermodynamic viability of different CO₂ capture processes.

The Thermodynamic Problem¶

The principles of thermodynamics set the minimum energy required to capture and separate CO₂ from other gases. Keep in mind that in the real world, the actual energy requirements are always higher - the thermodynamic minimum is the energy required in an ideal case without real world losses. We begin with a description of the problem:

- The atmosphere consists of many different gases, primarily N₂ and O₂. CO₂ is a trace atmospheric gas, taking up approximately ~0.04% by volume.

- The gas mixture in a smokestack of a coal combustion plant consist mainly of CO₂ (a few tens of %), H₂O, and N₂, with smaller amounts of CO, SO₂, NOₓ, and others.

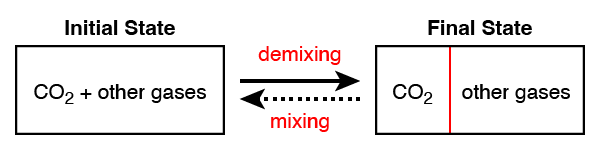

- The CO₂ capture process will separate CO₂ from the other gases, depicted in Figure 1.1.4.

Figure 1.1.4:Separating CO₂ from the other gases.

We can more precisely define our initial and final states. Thermodynamics does not define the time-dependent behavior of a system, so we can describe the problem using gas mixtures rather than flow rates. Specifically, we will consider a closed volume of gas, potentially with internal partitioning as shown above.

The initial states is a fixed volume of CO₂ and other gases. The final state has the same volume, but is divided into two partitions, with a barrier between which does not allow any gas to flow between them. Our goal is to calculate the absolute minimum amount of energy required to perform this separation; the best-case scenario. We will show later that any process requiring less energy is thermodynamically impossible and is therefore a perpetual motion machine.

One last note on notation: we will often consider thermodynamic state variables, which are variables which are an inherent characteristic of a system in a particular state. Examples of state variables include:

- Temperature ()

- Pressure ()

- Volume ()

- Gibbs free energy ()

- Enthalpy ()

- Entropy ()

Some other variables we will come across that are not state variables include:

- Heat ()

- Work ()

We will describe the total quantity of state variables using uppercase letters, for example is equal to the total internal energy in units of kJ. We will use a letter with a bar over it to represent a given quantity normalized by the system size, for example is the total energy of the system divided by the system size given by the number of moles of a given species , in units of kJ/mole. A lowercase letter represents the derivative of a given state variable with respect to , which is often referred to as the partial molar quantity. For example, is the partial molar internal energy, also given in units of kJ/mole.

The Ideal Gas Law¶

Before we introduce the First and Second Law of Thermodynamics, we first define an important relationship between the state variables of a gaseous system, namely pressure, volume, number of molecules, and temperature. The equation of state relating these variables is known as the Ideal Gas Law, which we will now derive.

Recall that pressure is defined as perpendicular force applied per unit area

and that momentum is defined as mass times velocity

Force is defined as the change in momentum , which combined with Equation (1.1.2) gives

where acceleration is equal to the time derivative of velocity . If the change in momentum occurs in discrete time steps, we can also define the force in terms of the average rate λ of these changes

where is the momentum transfer per event.

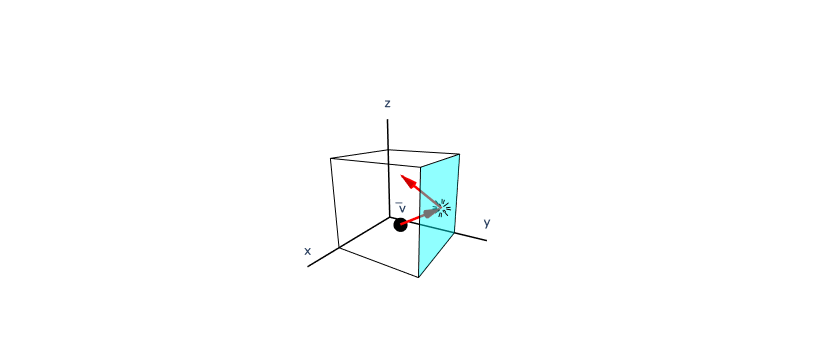

Figure 1.1.5:A single gas molecule inside a cube with side lengths and volume .

Now, consider a box containing gas molecules. As shown above in Figure 1.1.5, as each molecule bounces off the walls it will impart outward momentum to the walls. As we add more molecules to the box, the momentum transferred to the walls of the box will increase in proportion to the total mass of the gas. This transfer of momentum to the container walls is what we perceive as pressure. Next, we will derive the dependence of this pressure on the temperature and number of gas molecules .

First, we make some assumptions, which define an ideal gas:

- The molecule-wall collisions are elastic, meaning no energy is lost.

- The molecules are much smaller than the box.

- The molecules do not interact with each other.

First, we will calculate the force imparted by a single molecule along the -axis

The momentum change of the molecule along the -axis will be its final momentum minus its initial momentum, while the momentum change of the wall is the same value in the opposite direction

We can find the rate λ at which this molecule will hit the wall by considering how long it must travel between strikes. For a cube with side length , this rate is given by

The units of a rate should be events per second; checking the units here we get (length/time)/(length) = (1/time). If we combine these expressions, the force along the -axis becomes

We next expand this expression to the full 3D box and to total molecules, giving a total force

The total area of our box is equal to

We can combine these expressions with Equation (1.1.1) to get

where is the total box volume.

We next consider the internal energy of all molecules, which is equal to the sum of the kinetic energy of each molecule traveling with velocity

The total energy can be therefore be rewritten in terms of the the Expected value (average value) of translational kinetic energy over the population of all molecules

Combining Equations (1.1.11) and (1.1.13) gives

As a sanity check, we can confirm that has the same units as pressure

Rearranging Equation (1.1.14) we get

We next rescale to a more convenient value that is easier to work with, by recognizing that , i.e. the internal energy is proportional to temperature . We can also select a prefactor for which scales with the boiling and freezing points of water, defining

which is of course the temperature scale units of Centrigrade or Kelvins. With these units, we further define

This is the origin of the Boltzmann constant . This result ultimately comes from the equipartition theorem, which states that each degree of freedom contributes to the average energy, and the relationship between momentum transfer and pressure in kinetic theory. The molecules moving in 3 dimensions (and thus have 3 degrees of freedom) therefore contribute total energy.

If we substitute Equation (1.1.18) into (1.1.16), we get

The Boltzmann constant is related to another important constant, the universal gas constant , by a factor of Avagadro’s number (equal to one mole), giving

Here, Avogadro’s number represents the number of molecules in one mole, connecting the microscopic scale () to macroscopic quantities ().

We can then perform the final substitution into Equation (1.1.19) to get

Recognizing that

is the number of moles of gas molecules, we can write:

In summary, this equation relates the pressure , volume , number of molecules , and temperature of an ideal gas, and demonstrated that the pressure exerted on a container is due to the thermal motion of gas molecules.

- Oreskes, N. (2004). The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change. Science, 306(5702), 1686–1686. 10.1126/science.1103618

- Stainforth, D. A., Aina, T., Christensen, C., Collins, M., Faull, N., Frame, D. J., Kettleborough, J. A., Knight, S., Martin, A., Murphy, J. M., Piani, C., Sexton, D., Smith, L. A., Spicer, R. A., Thorpe, A. J., & Allen, M. R. (2005). Uncertainty in predictions of the climate response to rising levels of greenhouse gases. Nature, 433(7024), 403–406. 10.1038/nature03301

- Zhang, X., Zhao, H., Yang, Q., Yao, M., Wu, Y., & Gu, Y. (2023). Direct air capture of CO2 in designed metal-organic frameworks at lab and pilot scale. Carbon Capture Science & Technology, 9, 100145. 10.1016/j.ccst.2023.100145