3.3 Phases of Water

Understanding phase transitions is critical in applications like geothermal power, heat engines, and even planetary atmospheres. In the next sections, we will explore the role of phase changes in engineering applications.

The Three Phases of Water¶

Water is essential to all known forms of life and one of the most abundant substances on Earth, covering over 70% of the planet’s surface. It also plays a critical role in thermodynamics as the working fluid in many heat engines due to its high heat capacity, phase transition properties, and non-toxicity.

Water exists in three phases:

- Solid (ice)

- Liquid (water)

- Gas (water vapor).

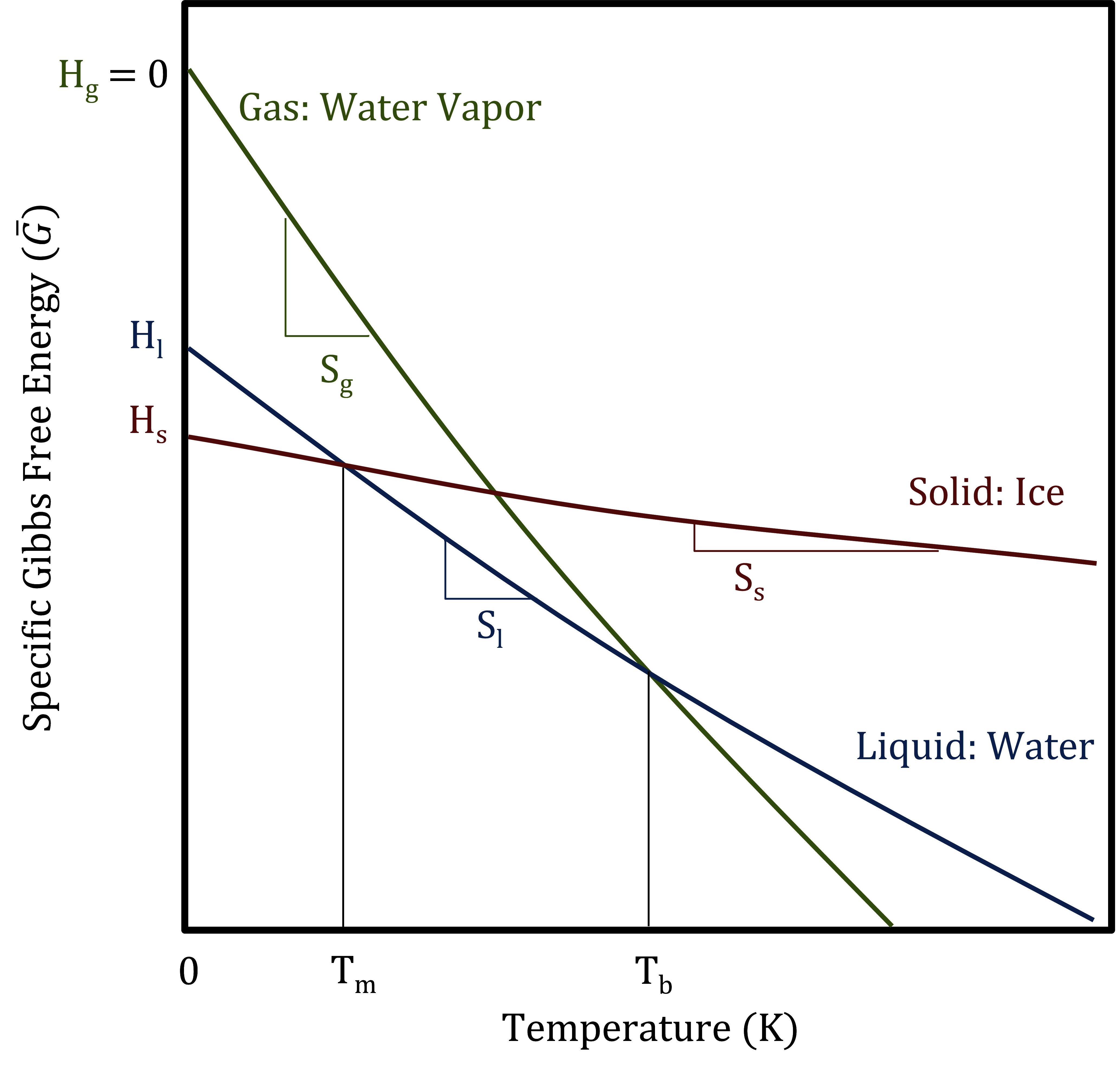

The stability of each phase depends on temperature and pressure, which can be analyzed through the specific Gibbs free energy of water, shown in Figure 3.3.1. A specific quantity is represented with a bar over the variable, and is equal to that quantity divided by the number of mols , for example Equation (2.3.17) derived an expression for the Gibbs free energy, which has a specific quantity equivalent:

where is the specific enthalpy, is temperature, and is the specific entropy . The slope of is equal to , and the y-intercept represents . To simplify, we assume and do not depend on temperature.

Figure 3.3.1:The specific Gibbs free energies for the three phases of water as a function of temperature . The phase with the lowest value of at a given is stable.

Enthalpy & Bond Energy¶

The enthalpy of each phase represents the strength of intermolecular bonds, and is given by the y-intercept of Figure 3.3.1. Since water molecules in the solid phase (ice) are strongly hydrogen-bonded in a crystalline lattice, their enthalpy is lower than in liquid water, where the molecules move more freely due to their weaker chemical bonds. In the gaseous phase, the molecules are unbound and have the highest enthalpy. We can represent this relationship as

During melting, heat is absorbed to break intermolecular bonds to transform from the solid to the liquid phase. Similarly, vaporization from the liquid to the gas phase requires additional energy input to separate molecules into a gas. Both processes are endothermic.

Entropy & Molecular Disorder¶

Entropy measures molecular disorder. In solid ice, molecules are arranged in a fixed lattice which is highly regular. In liquid water, the molcules are close together but able to move somewhat freely. In a gaseous water vapor, the molecules are highly disordered and move independently. This explains why the slope of shown in Figure 3.3.1 is most negative for gases, less negative for liquids, and least negative for solids. We can quantify this ordering as

Entropy is always positive because it represents the number of ways molecules can be arranged. The relative entropy differences affect phase behavior.

Phase Stability & Transitions¶

A system in equilibrium minimizes Gibbs free energy, as we saw in the Chemical Equilibrium chapter. At the different temperatures shown in Figure 3.3.1, the most stable phase is the one with the lowest :

| Ice is stable. | |

| Ice and liquid water coexist (melting point). | |

| Liquid water is stable. | |

| Liquid water and vapor coexist (boiling point). | |

| Water vapor is stable. |

At phase transition points (melting or boiling), two phases coexist in equilibrium, meaning their Gibbs free energies are equal:

A few notes for advanced readers:

Supercooled liquid water can exist below , but it is not in equilibrium and will freeze if nucleation sites become available. See Supercooling for more information.

Water ice can also directly transform into the gas phase at low partial pressures, a process known as sublimination. See sublimation for more information.

There are actually at 19 known phases of solid crystalline water ice. When we colloquially talk about water ice, we typically mean the hexagonal form of ice stable at ambient pressure below C known as . See Ice and Phases of ice for more information.

Phase Transitions in Water¶

Gibbs Energy of Boiling¶

At phase transition temperatures, heat is added or removed without changing temperature, leading to a transformation between phases. Consider boiling liquid water into vapor in an isolated system.

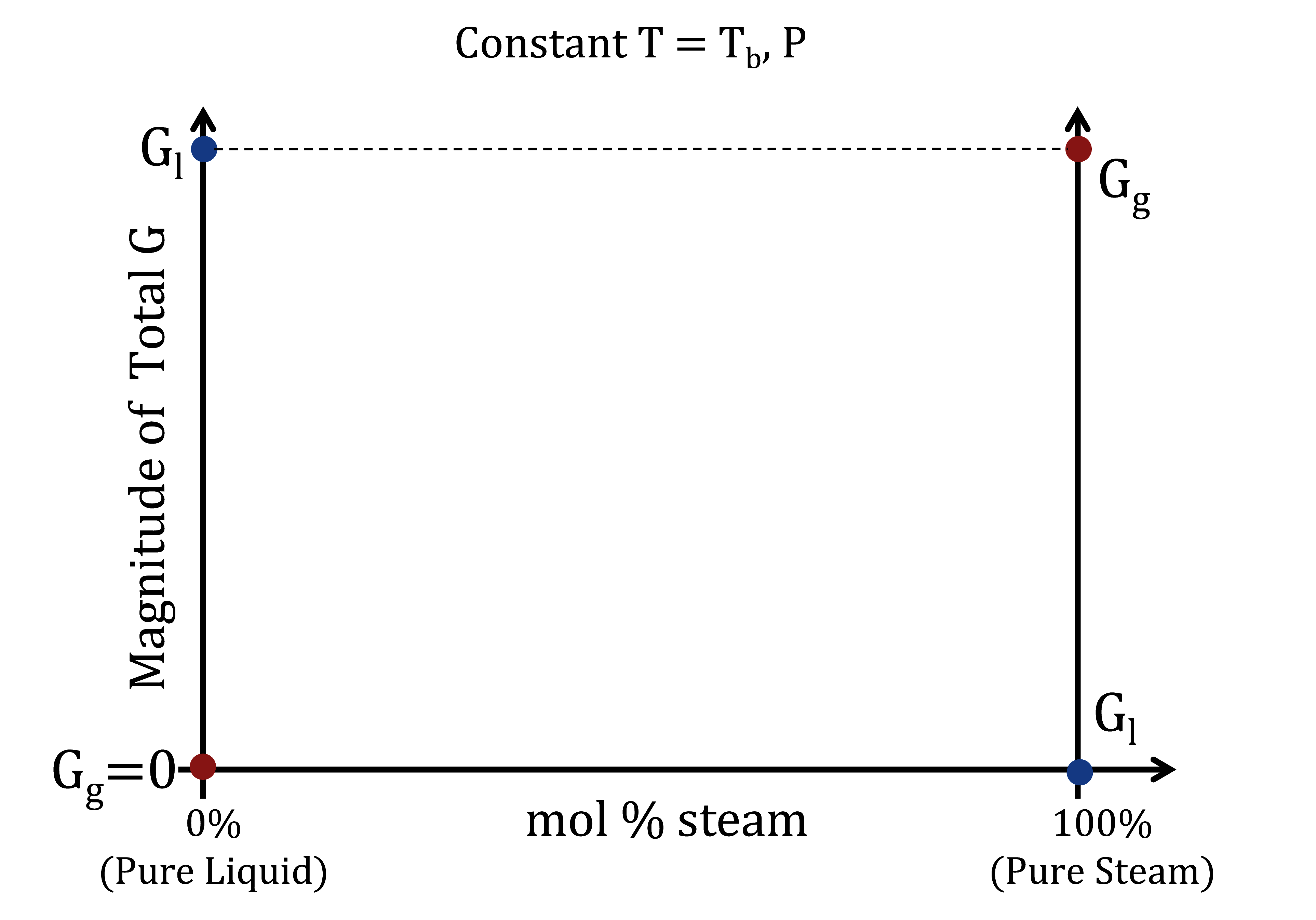

Figure 3.3.2 shows the total Gibbs free energy before and after boiling. Initially, the system contains only liquid water. As boiling progresses, liquid converts to gas, and the system moves toward 100% vapor.

Figure 3.3.2:Magnitude of Gibbs free energy before and after boiling. The sign of the Gibbs free energy depends on the value of enthalpy as the reference state.

Since boiling occurs at constant temperature and pressure, the Gibbs free energy change is:

At constant and , this simplifies to:

where is the chemical potential of species . The chemical reaction which represents the coexistence of the liquid and gas phases of water is

We can write the total variation in Gibbs energy as the combination of variation in the liquid and gas phases:

Additionally, at equilibrium the chemical potentials of coexisting phases must be equal:

Since the total number of molecules remains constant:

Substituting these conditions:

You may wonder how the chemical potentials can be the same, yet the values of have opposite sign. The answer lies in the molar change values . These values must have opposite sign, since each mol of boiling water will reduce the number of liquid phase molecules by 1 mol, while increasing the number of gas phase molecules by 1 mol.

The above derivations show that at equilibrium, the total Gibbs free energy does not change as long as temperature and pressure remain constant.

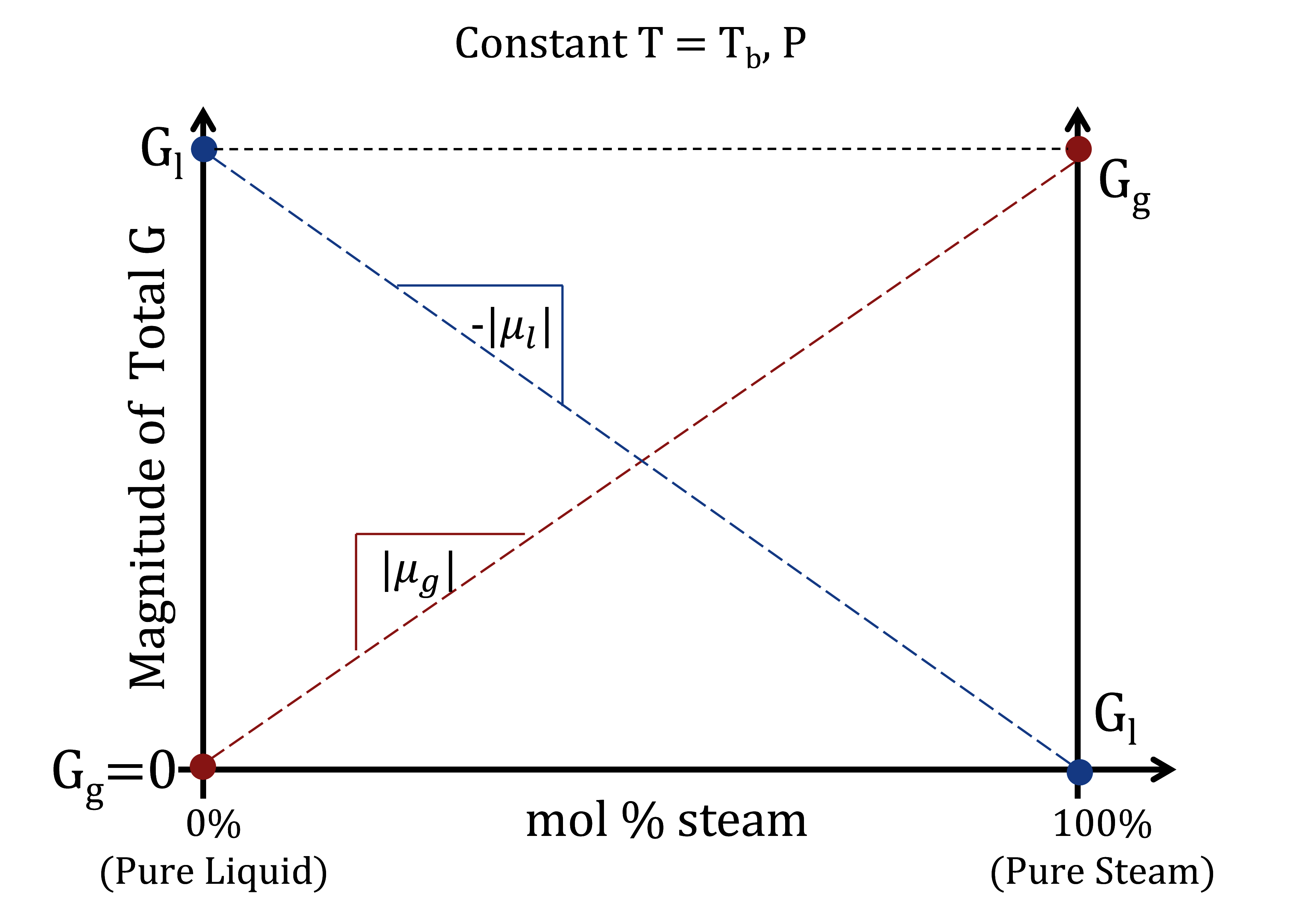

We can now complete Figure 3.3.2. During boiling, the Gibbs free energy of both phases will vary following Equation (3.3.12). This is shown schematically in Figure 3.3.3.

Figure 3.3.3:Magnitude of Gibbs free energies during boiling.

As liquid water boils, its total Gibbs free energy decreases proportionally to the number of mols in the liquid phase. Simultaneously, water vapor forms and its Gibbs free energy increases. However, since the chemical potentials are equal at , the total Gibbs free energy remains constant.

Gibbs Energy of Freezing¶

The Gibbs energy path during the transformation of liquid water to solid ice is more complex than that of boiling. The primary reason is that transformation to solid ice requires nucleation of tiny initial crystalline grains of ice. The extra energy required for this process means that in practice, typically liquid water may need to be supercooled to below the freezing point before the transformation can begin. These complexities however are beyond the scope of this course.