3.5 Evaporation

Evaporation versus Boiling¶

In the last section, we learned that heating water above its boiling temperature converts it to a gas. This boiling process is characterized by the formation of vapor bubbles within the liquid. However, liquid water can also transition to a gas at temperatures well below its boiling point. If a glass of water is left out in open air, it will eventually disappear as it evaporates into water vapor.

Why does water evaporate at room temperature, even though liquid water is the thermodynamically stable phase at that temperature? To answer this, we must distinguish boiling from evaporation.

- Boiling occurs at the boiling point when vapor bubbles form inside the bulk liquid. This is a nonequilibrium process that proceeds rapidly as the system tries to reach equilibrium.

- Evaporation occurs at any temperature, as individual molecules at the liquid surface escape into the gas phase. This is an equilibrium process.

The key difference is kinetic: boiling occurs when the bulk liquid temperature surpasses , while evaporation occurs continuously due to molecular motion.

Evaporation in a Closed System¶

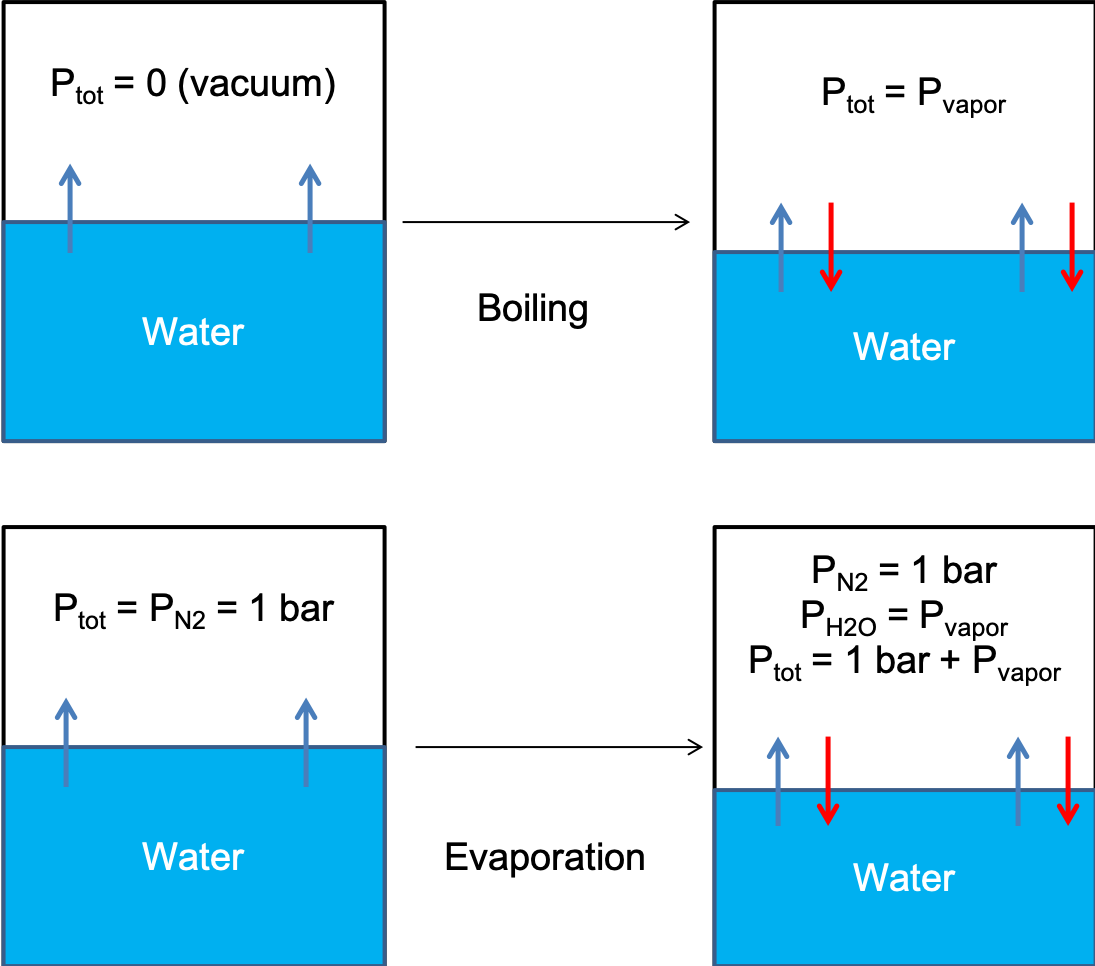

To better understand evaporation, consider a sealed jar of water at room temperature inside a vacuum chamber, shown at the top of Figure 3.5.1. Initially, there is only liquid water and vacuum.

Figure 3.5.1:(top) Water boiling in a vacuum. (bottom) Water evaporating into a dry environment. In both cases, water boils / evaporates into water vapor, until the system reaches equilibrium. This is shown schematically when evaporation (blue arrows) and condensation (red arrows) occur at the same rate.

If the vacuum is perfect, the boiling temperature of water is near absolute zero according to the Clausius-Clapeyron relationship given in Equation (3.4.19) and shown in Figure 3.4.1. Even if the vacuum is not perfect, the boiling temperature is below room temperature, so the liquid water begins to boil into vapor.

Over time, enough water evaporates to raise the vapor pressure to an equilibrium value, . At equilibrium, the evaporation rate equals the condensation rate, and the chemical potential of liquid and vapor water are equal:

At this point, no net evaporation occurs, even though molecules still transition between phases.

Evaporation in an Open System¶

Now, consider replacing the vacuum with dry nitrogen gas at room temperature, shown at the bottom of Figure 3.5.1. The temperature of the water is still well below 100°C, so we do not expect boiling. However, water at the surface still evaporates, because some molecules at the interface have enough energy to escape into the gas phase.

Since the gas contains only nitrogen, no condensation occurs at first. Over time, water molecules accumulate in the gas phase. This causes partial pressure of water vapor to increase. Eventually, the water vapor reaches the equilibrium vapor pressure, and condensation begins. At equilibrium, the evaporation rate equals the condensation rate just as in the vacuum case.

Vapor Pressure¶

The (partial) vapor pressure of water, , is the equilibrium partial pressure at which the rate of evaporation equals the rate of condensation. For a given temperature, can be determined using the same derivation as the Clausius-Clapeyron equation, since at equilibrium . Thus, the equilibrium vapor pressure follows:

where is the heat of evaporation, equivalent to the latent heat of boiling. Is positive because breaking the intermolecular bonds of liquid water requires heat. This equation describes how vapor pressure changes with temperature.

Note how we are using the same expression to describe both boiling and evaporation. This is because the relationship between equilibrium temperature and pressure follows the same physics both both cases. The Clausius-Clapeyron relationship is a differential equation, relating the change of pressure and temperature, but does not itself specify the temperature.

Continuous Evaporation in an Open System¶

If we constantly replenish the nitrogen with fresh, dry gas, water will continue evaporating indefinitely. This is because the evaporated water molecules are carried away before condensation can occur. Given enough time, all liquid water will evaporate at room temperature.

This observation helps us define boiling more strictly:

- Boiling occurs when the vapor pressure exceeds the surrounding pressure.

- At 100°C and 1 atm, atm, and water boils.

- In an open system, evaporation continues as long as , and will only stop if the surrounding gas becomes saturated with water vapor.

This is why Gibbs’ phase rule applies even to nonequilibrium processes: the final state of boiling or evaporation still satisfies equilibrium conditions.

Why Sweating Cools the Body¶

Sweating cools the body because evaporation absorbs heat from the skin. The energy required to break intermolecular bonds and transition water molecules into the gas phase comes from body heat, lowering skin temperature.

However, on a humid day, when the partial pressure of water vapor in the air approaches the equilibrium vapor pressure, evaporation slows down. This explains why humid heat feels hotter; less sweat evaporates, and therefore the body struggles to dissipate heat.

Vapor Pressure and Humidity¶

The west coast of the US is drier than the east coast, despite both being near an ocean. This is due to differences in equilibrium vapor pressure. Over the ocean, water vapor is in equilibrium with liquid water, meaning:

The relative humidity is defined as:

Over the ocean, . However, when air moves over land, stays the same, but changes with temperature, altering RH. We can use these observations to explain why the East Coast More Humid.

The Gulf Stream warms the Atlantic, increasing and humidity. The Pacific is cooler, lowering and RH. These effects are summarized below.

| Coastline | Ocean Temp () | Equilibrium | Relative Humidity (RH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| West Coast | Lower | Lower | Lower |

| East Coast | Higher | Higher | Higher |

Warmer oceans lead to more water vapor in the air, increasing humidity. Cooler oceans have the opposite effect, explaining the difference between the US coasts.