3. Geothermal Energy and Heat Engines

In Module 2, we explored fuel cells as a way to convert chemical energy into electricity. While highly efficient, fuel cells require a steady fuel supply, such as hydrogen, which is rare in nature. Most hydrogen is produced via methane reformation, releasing carbon dioxide in the process. Some fuel cells run directly on methane, but they also emit CO₂, contributing to global warming.

A clean and abundant energy source is heat from the Earth’s core, about 6400 km below us. This heat comes from two main sources: residual heat from planetary formation and radioactive decay. The Earth’s core, at 4000–7000 K, radiates about TW of power Davies & Davies, 2010. This far exceeds global energy consumption, which is approximately 20 TW (the World Energy Outlook 2023 estimated consumption in 2022 to be 630 exajoules, giving 630e18 / 31.5e6 seconds in each year ≈ 20 TW). However, extracting this energy efficiently everywhere is impractical, so we focus on locations where high-temperature reservoirs exist closer to the surface.

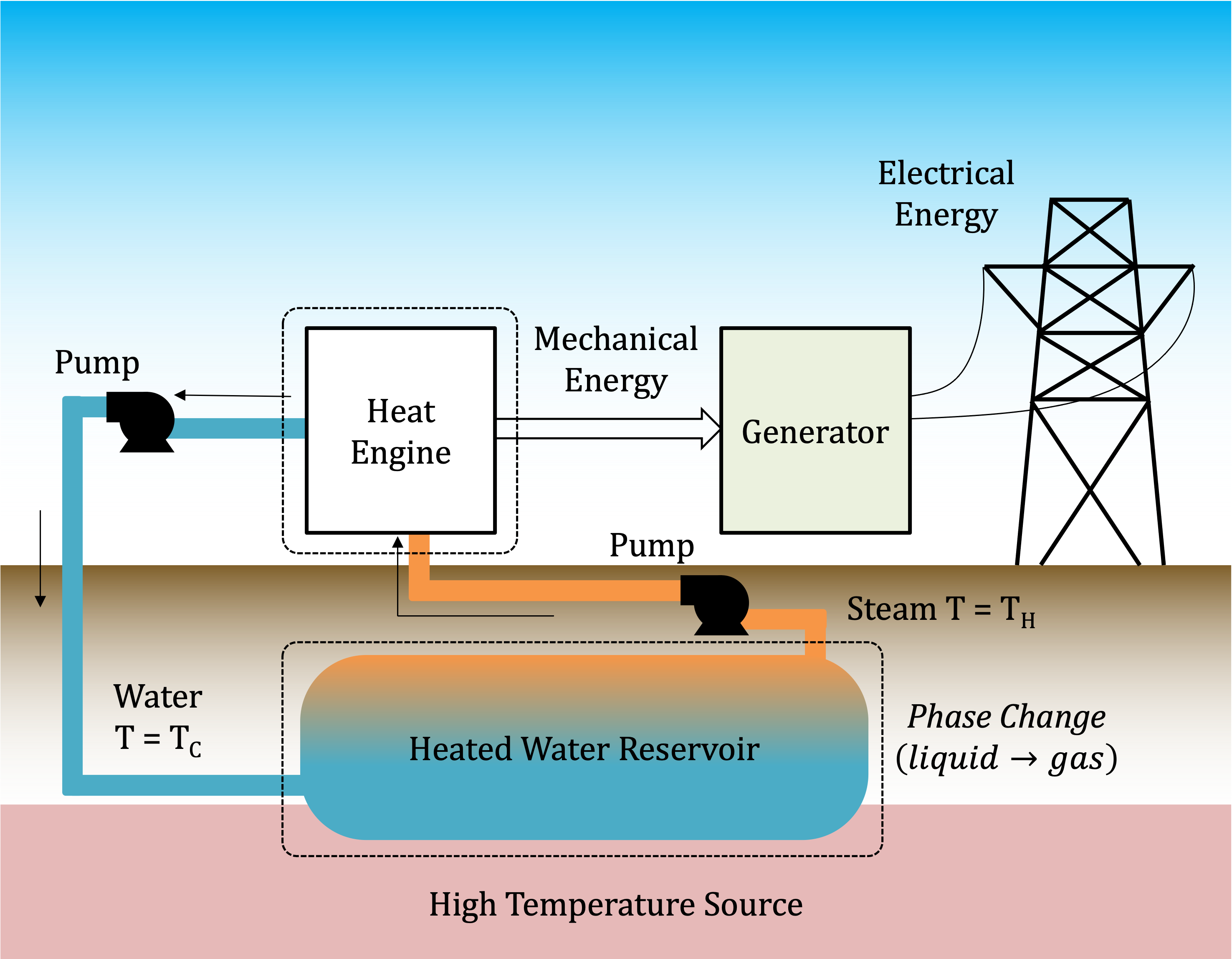

Figure 3.1:Schematic of a geothermal power plant.

Geothermal energy is most accessible in regions with volcanic activity, where shifting tectonic plates create pathways for heat to reach the surface. Examples include hot springs like Iceland’s Blue Lagoon and geysers like Yellowstone’s Old Faithful. Depending on depth, geothermal systems operate at different temperatures: shallow reservoirs help heat and cool buildings (like Stanford’s Central Energy Facility), mid-depth systems access temperatures over 100°C for electricity generation, and deep “super-hot-rock” geothermal can exceed 373°C, reaching the supercritical phase for even greater efficiency.

At a geothermal power plant, heat from underground reservoirs boils water or another working fluid, producing steam that drives a heat engine. This engine converts thermal energy into mechanical work, which a generator then transforms into electricity via electromagnetic induction.

As shown in Figure 3.1, a geothermal plant has two key components: (1) a phase transition, where liquid water turns into steam, and (2) a heat engine that converts thermal energy into work. This module is divided into these two topics. We will use the Carnot engine as a model for heat engines and discuss phase transitions separately. A full thermodynamic cycle, such as the Rankine cycle used in real geothermal plants, is beyond the scope of this course. Those interested in more advanced heat engine cycles may wish to explore thermodynamics courses in mechanical engineering.

- Davies, J. H., & Davies, D. R. (2010). Earth’s surface heat flux. Solid Earth, 1(1), 5–24. 10.5194/se-1-5-2010