3.1 The Carnot Engine

A geothermal power plant needs a way to convert heat into work and, ultimately, electricity. A heat engine performs this conversion. In this section, we discuss the Carnot engine, the most efficient heat engine possible.

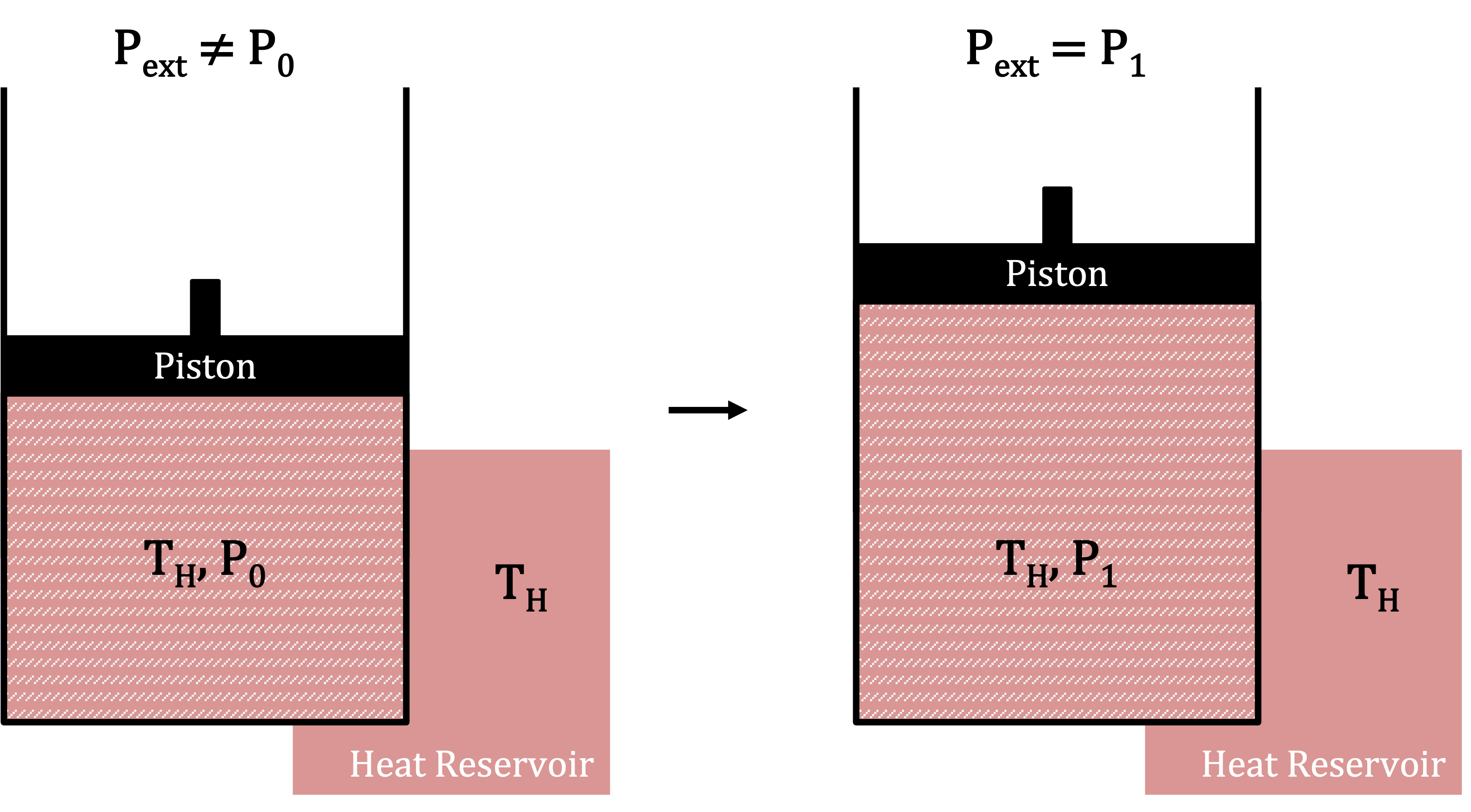

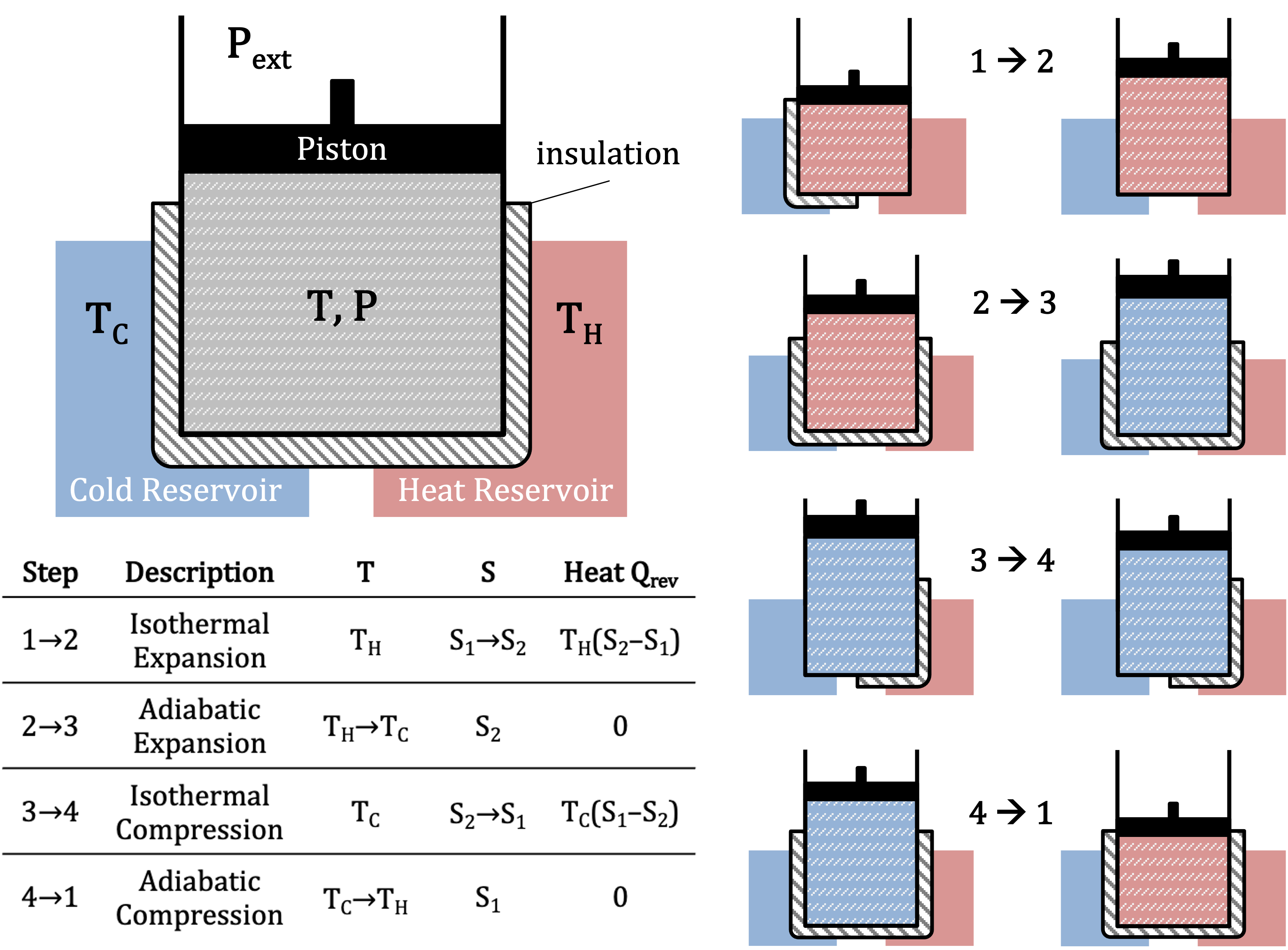

Figure 3.1.1:Isothermal expansion of a piston connected to a heat reservoir. The walls of the piston allow heat transfer, but not exchange of matter.

Isothermal Expansion of Gas¶

To understand the Carnot engine, we first consider a piston in contact with a heat reservoir, shown in Figure 3.1.1. The piston walls allow heat transfer but are impermeable to matter. The temperature inside the piston matches the reservoir, but the pressure is higher than the surroundings. As a result, the gas expands, pushing the piston outward and doing work while maintaining a constant temperature. This process is called isothermal expansion.

We assume the expansion happens quasistatically, meaning the external pressure is only slightly lower than the internal pressure at every step. The behavior of the gas follows the ideal gas law:

Since n and T are constant, we get:

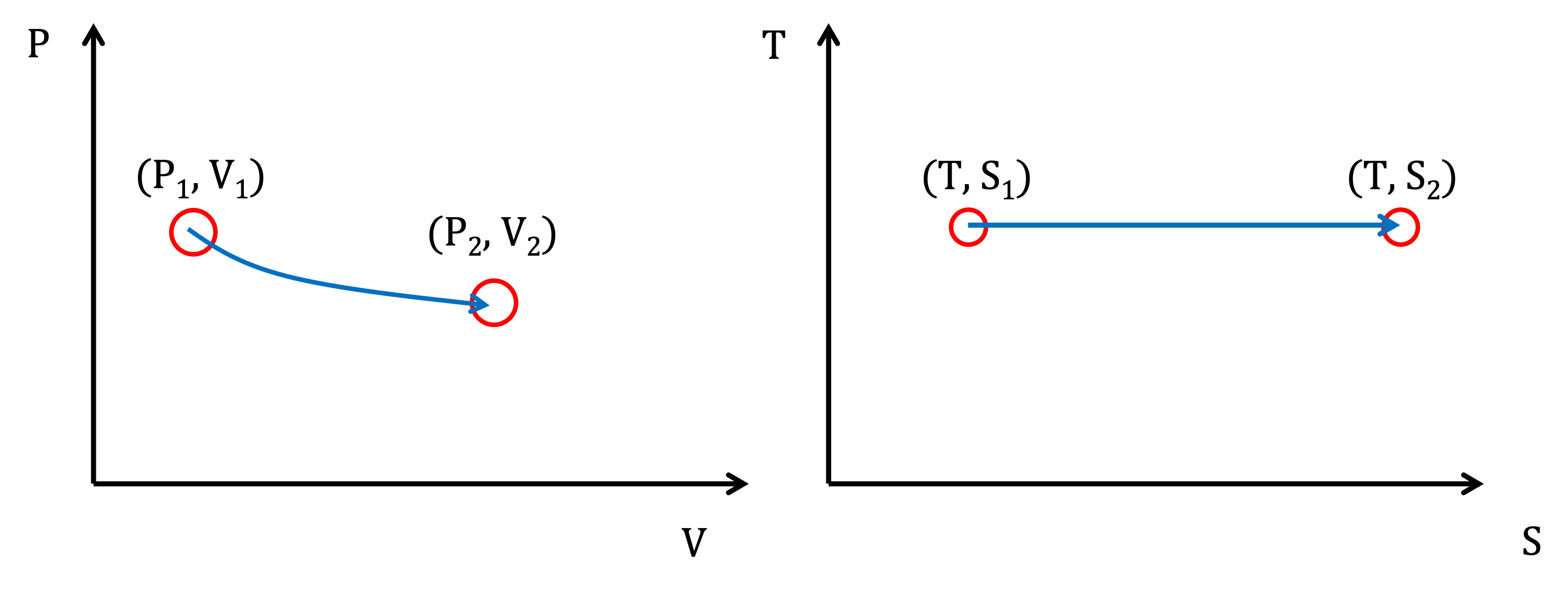

Figure 3.1.2:The change of pressure, volume, entropy and temperature during isothermal gas expansion.

The left panel of Figure 3.1.2 shows the relationship between pressure and volume. Recalling Equation (1.2.5), we know that the work done by the gas during expansion is:

The expanding gas is doing work, which can be harvested through the motion of the piston. Since energy is conserved, the heat absorbed from the reservoir equals the work done by the gas:

For a reversible process, we know from Equation (1.3.7) that heat transfer is given by:

Therefore, the entropy of the gas must increase as it expands. This agrees with what we learned in Defining the Second Law: lower pressure corresponds to higher disorder (entropy).

If the piston expands indefinitely, we would have a system converting heat entirely into work with 100% efficiency. However, to continuously extract work, the piston must return to its original state. To restore the system, we compress the gas back to its original temperature and pressure. During compression, work is done on the gas.

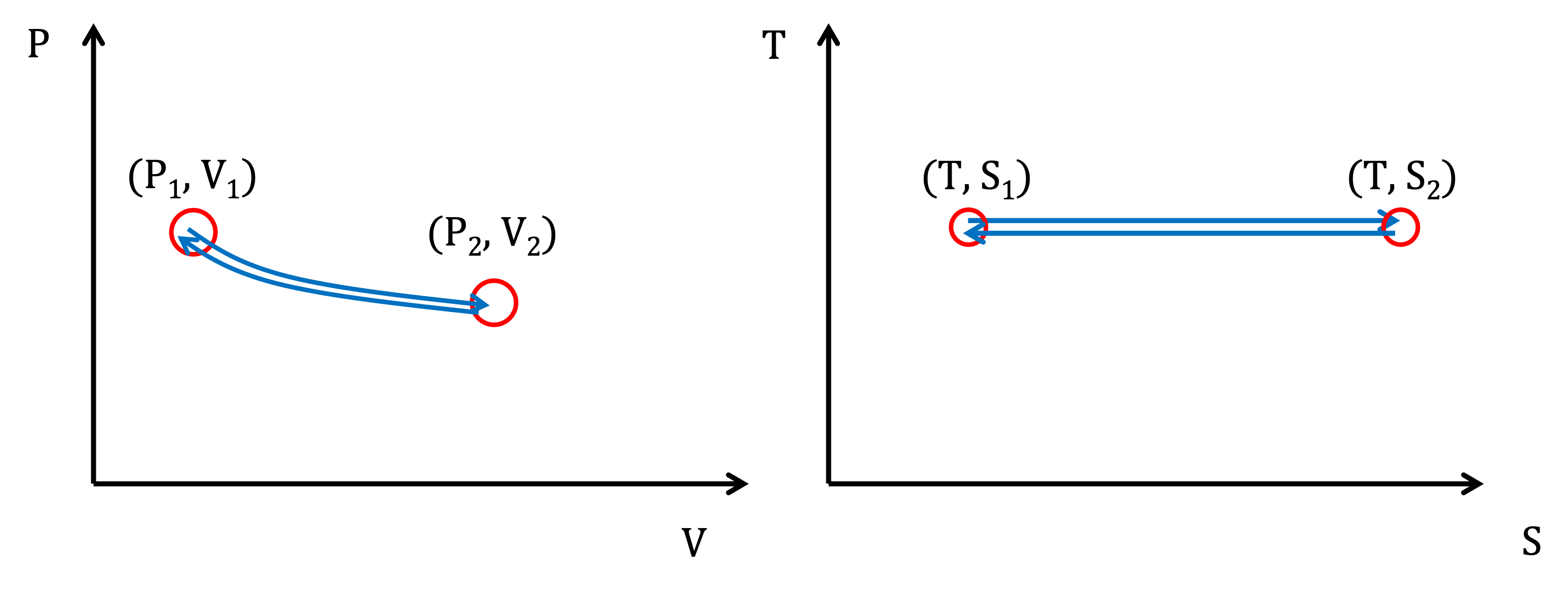

The right panel of Figure 3.1.3 shows the piston’s expansion and compression cycle. Starting from initial values of , the piston expands to , and then returns to . The left panel of Figure 3.1.3 shows the T-S diagram during this cycle. Starting from initial values of , the piston expansion increases the entropy to , and then its compression returns the system to .

Figure 3.1.3:Isothermal expansion and then compression of a piston. Each cycle performs no net work.

Graphically, integrating in Figure 3.1.3 does not generate any net work since expansion and compression steps cancel each other out. A complete isothermal cycle can be modeled by the expression

where the symbol represents a closed path integral, indicating that the system undergoes a full cycle and returns to its initial state.

Similarly, the heat absorbed from to exactly equals the heat released as we traverse back from to . Thus we have no net conversion of heat to work. This means the total work done by the gas during expansion cancels out the work required to compress it. Similarly, the heat absorbed during expansion equals the heat released during compression:

Thus, no net heat is converted to work.

The Carnot Cycle¶

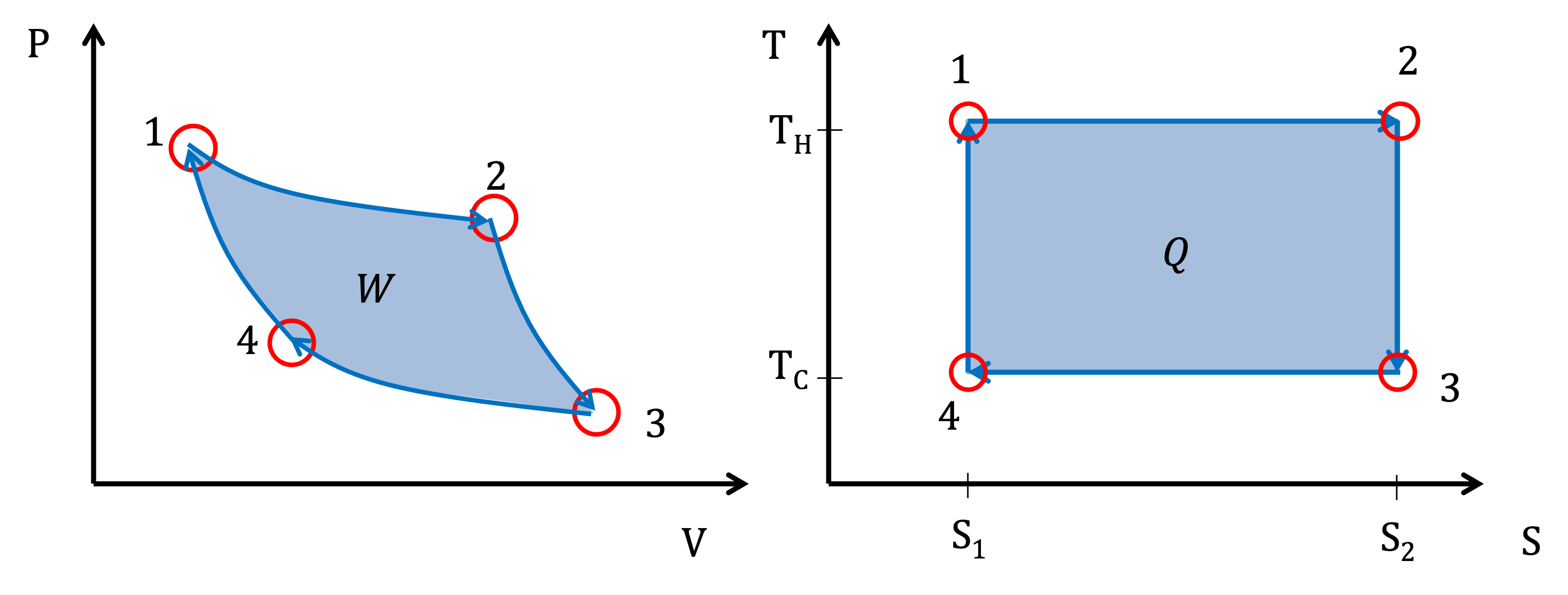

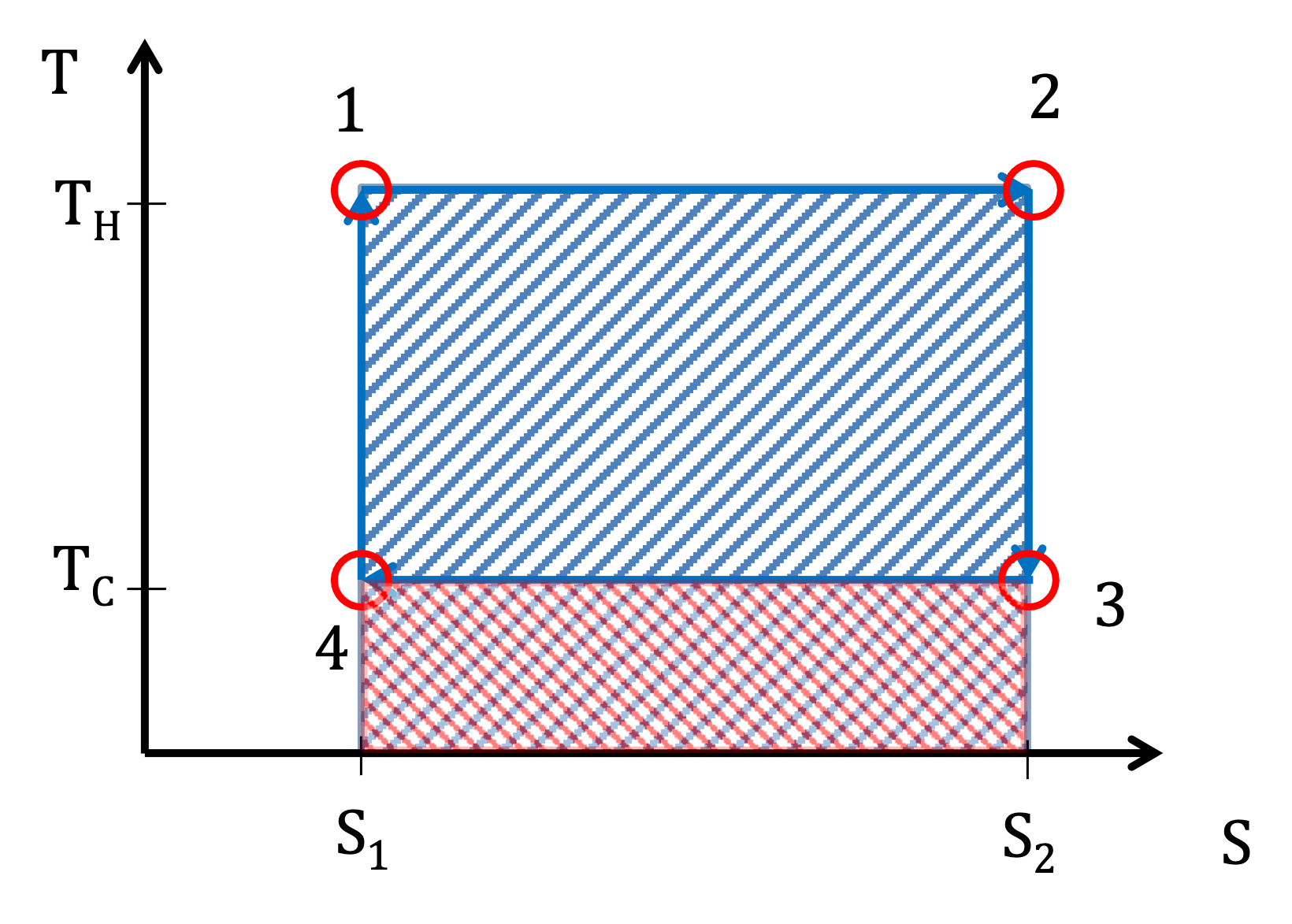

To extract net work, the work done by the gas must exceed the work required to restore the system. This means that more heat must be absorbed during expansion than is released during compression. Considering Equation (3.1.5), to absorb more heat while keeping the entropy the same at the start and end of the cycle, we must increase temperature during expansion and decrease temperature during compression. This creates a complete cycle, plotted in Figure 3.1.4.

Figure 3.1.4:The P-V and T-S diagrams for the Carnot cycle.

The left panel of Figure 3.1.4 shows the pressure-volume (P-V) diagram, while the right panel shows the temperature-entropy (T-S) diagram. The four steps of the Carnot cycle are:

- Isothermal Expansion (1 → 2): The gas expands at high temperature , absorbing heat.

- Adiabatic Expansion (2 → 3): The gas expands without heat transfer, cooling to .

- Isothermal Compression (3 → 4): The gas is compressed at , releasing heat.

- Adiabatic Compression (4 → 1): The gas is compressed without heat transfer, raising its temperature back to .

Since adiabatic expansion and compression involve no heat exchange , we can ignore steps 2 and 4 and use:

The total work done by the cycle is:

We define efficiency η as:

We could use Equation (1.2.5) to calculate the work done, but there is an easier way. We can instead use the First Law and our knowledge that the cycle begins and ends at the same temperature:

We therefore only need to sum up all net contributions to , which is shown in Figure 3.1.5.

Figure 3.1.5:The 4 steps of the Carnot cycle shown for a piston, with the associated changes in , and heat for all steps.

The net heat transferred (and therefore work performed) is therefore equal to:

The efficiency of the Carnot cycle simplifies to:

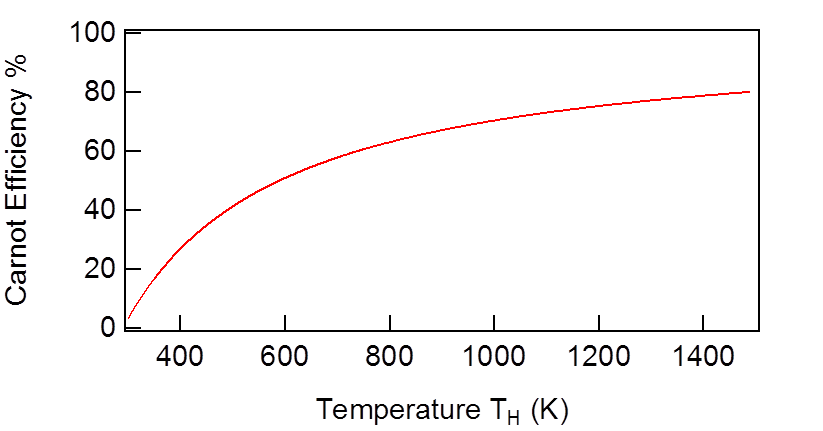

This is the Carnot efficiency, the maximum efficiency of an ideal heat engine which alternates between two temperatures (in units of Kelvins). This efficiency is shown graphically in Figure 3.1.6. The Carnot efficiency for a cold reservoir at 300K is plotted in Figure 3.1.7.

Figure 3.1.6:Heat input vs work output for the Carnot Cycle.

Figure 3.1.7:The Carnot efficiency at 300K, as a function of the hot reservoir temperature.

Irreversibility and Efficiency¶

The Carnot cycle is an ideal process, but real-world engines always have some irreversible components. Any deviation from perfect reversibility lowers efficiency.

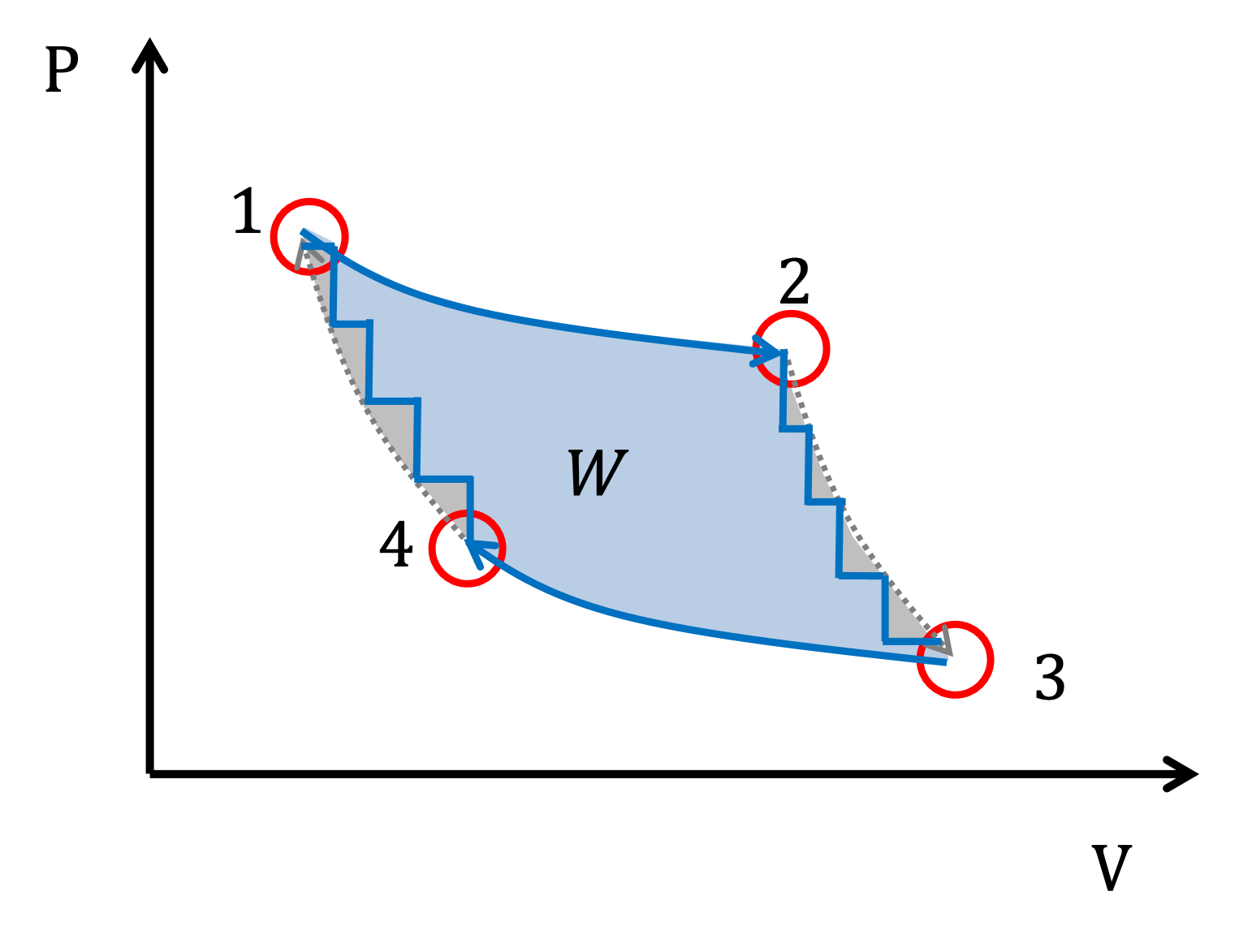

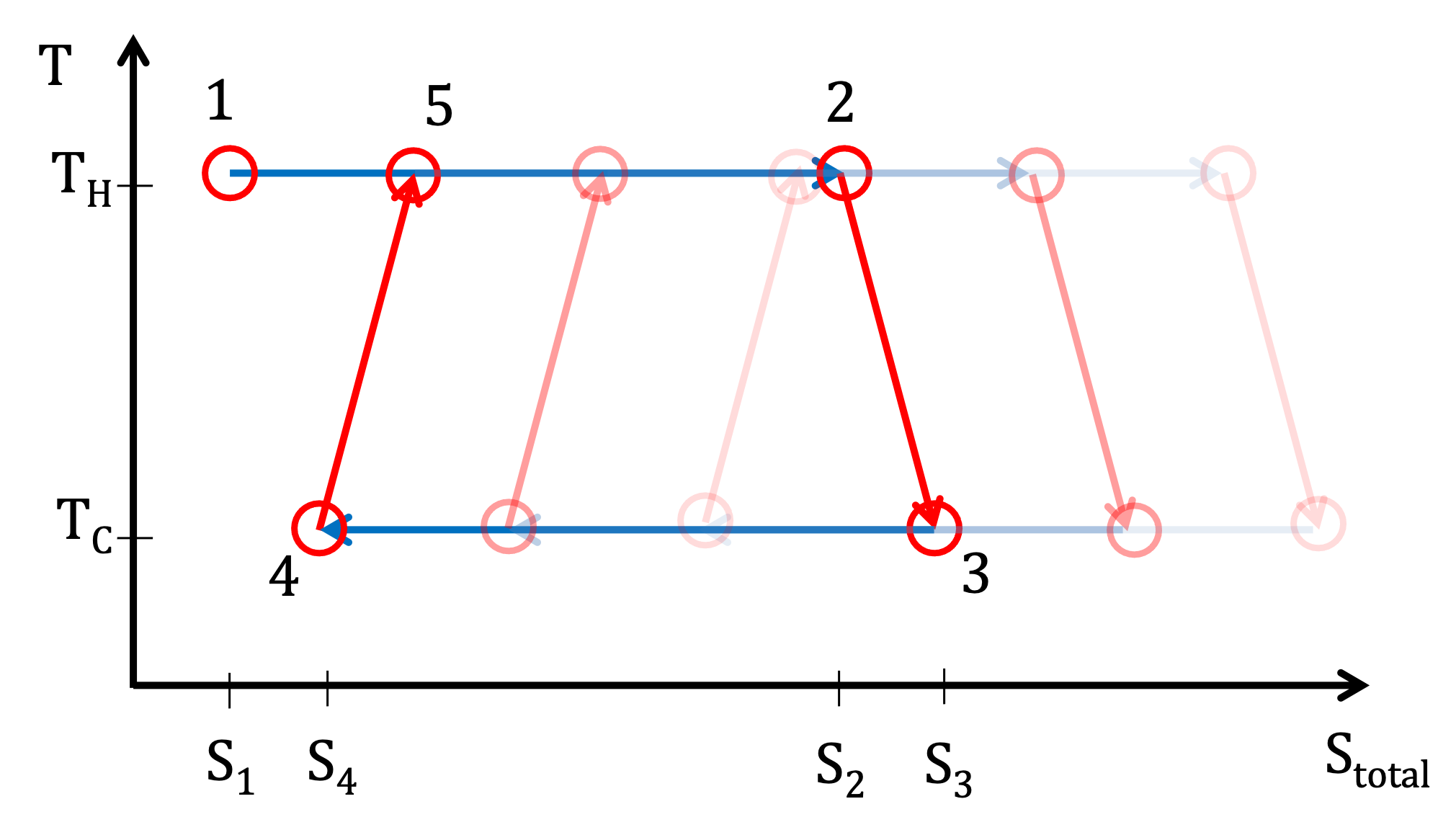

For instance, consider a modification where the adiabatic steps (2 → 3 and 4 → 1) are not reversible. Instead of quasistatic changes in pressure and volume, real processes often involve stepwise changes, as shown in Figure 3.1.8.

Figure 3.1.8:The P-V diagram of an approximate Carnot cycle which includes non-quasistatic adiabatic steps.

If we again consider the process shown in Figure 3.1.1, we know that in the real world when external pressure changes suddenly, the piston volume takes time to adjust. Friction and turbulence cause energy losses, reducing efficiency:

We can analyze this efficiency loss in terms of entropy. For a reversible process:

But for an irreversible process:

Thus, entropy increases, meaning some energy is lost as waste heat each cycle. This is shown schematically in Figure 3.1.9. Each change in temperature is accompanied by a slight increase in entropy of the universe, which causes a decrease in the efficiency loss. We could perform a similar analysis for Figure 3.1.8.

Figure 3.1.9:A non-ideal thermodynamic cycle where the entropy of the system increases slightly at steps (2 → 3) and (4 → 1).

The Carnot cycle sets the upper limit on efficiency. Any real cycle with irreversible steps will be less efficient, as energy is lost due to friction, turbulence, and heat dissipation.