3.2 The Carnot Theorem

Heat Pumps¶

A heat pump is essentially a heat engine operating in reverse. Instead of converting heat into work, it consumes work to transfer heat from a cold reservoir to a hotter one. Examples include air conditioners, refrigerators, and building heating systems.

Unlike heat engines, where efficiency measures how much work is extracted from heat, heat pumps are rated by how much heat they can transfer for a given amount of work. Using the same efficiency definition from Equation (3.1.10), we write:

For a heat pump, we aim to maximize heat transfer while minimizing work. A lower value of η means the system can transfer more heat using less work. A heat pump with η = 0 would violate the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

To quantify this performance, heat pumps are characterized by their coefficient of performance (COP), which is the inverse of efficiency:

A high COP indicates an efficient heat pump, capable of transferring large amounts of heat for minimal work. A high efficiency heat engine maximizes η, which means it derives the most work from heat.

Stacking a Carnot Heat Engine and a Heat Pump¶

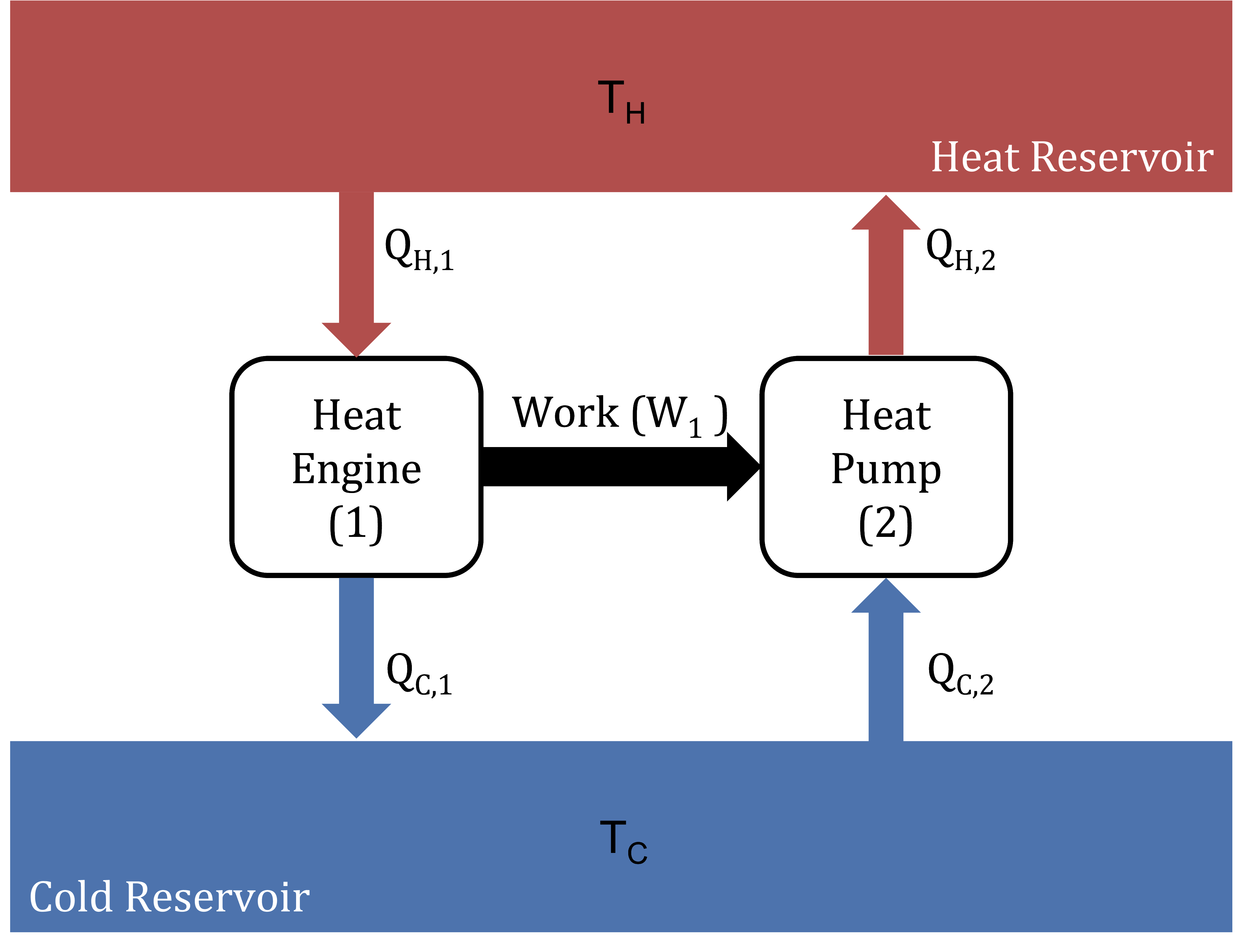

Consider the system plotted in Figure 3.2.1, where a Carnot heat engine is connected to a Carnot heat pump. The heat engine extracts energy from a hot reservoir and rejects heat to a cold reservoir while generating work. This work is then used by the heat pump to transfer heat from the cold reservoir back to the hot reservoir. We will use the subscripts 1 and 2 to refer to the heat engine and heat pump respectively.

Figure 3.2.1:A heat engine which produces work to power a connected heat pump. and Q are positive because heat flows in, whereas Q and Q are negative as heat flows out.

For the heat engine in Figure 3.2.1 the First Law of Thermodynamics states:

where is negative because heat is transferred to the cold reservoir. The engine efficiency is:

Rearranging:

The heat pump by contrast consumes work equal to that generated by the heat engine, and therefore

Similarly, is negative and is positive. We can write these in terms of the heat pump efficiency

Summing heat flows at the hot and cold reservoirs:

These expressions give the net heat flows out of the hot reservoir to the heat engine and pump, and the net heat transferred from the cold reservoir to the heat engine and pump.

Case Studies of a Carnot Engine and a Heat Pump¶

Now, we examine different scenarios by varying the efficiencies of the heat engine and heat pump shown in Figure 3.2.1. The Carnot engine operates at the highest possible efficiency for any heat engine. Anything more efficient would be a perpetual motion machine, violating the Second Law by spontaneously transferring heat from cold reservoirs to hot without external work.

Case 1: Both Devices Operate at Carnot Efficiency¶

If both the heat engine and heat pump operate at Carnot efficiency ():

Since there are no net heat flows, the total system entropy remains constant, making it a fully reversible process. This system is highly idealized, but does not violate the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics because entropy of the system remains constant.

Case 2: Heat Engine Efficiency Below Carnot¶

Next we consider a realistic heat engine. If and , which gives heat flows equal to

This results in heat flowing out of the hot reservoir and heat flowing into the cold reservoir. There is a net increase in entropy as heat flows irreversibly from hot to cold, and thus obeying the 2nd law.

Case 3: Heat Engine Efficiency Exceeds Carnot¶

Now lets consider the case where and , which leads to:

This scenario highlights an important conclusion: if a heat engine were to operate more efficiently than the Carnot limit, it would enable a net transfer of heat from the cold reservoir to the hot reservoir without any external work. This directly contradicts the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which states that heat cannot spontaneously flow from a colder body to a hotter one without external energy input.

More generally, this means that any heat engine must have an efficiency less than or equal to the most efficient possible heat pump operating between the same temperature reservoirs. That is:

Since we know that a Carnot heat pump exists with efficiency , then we must have:

This leads us to the Carnot Theorem:

Any engine exceeding the Carnot efficiency would violate the Second Law of Thermodynamics, as it would enable heat to flow spontaneously from a colder reservoir to a hotter one without external work. Furthermore, all reversible heat engines operating between the same two reservoirs must have the same efficiency, regardless of the working substance or cycle details.

This conclusion reinforces the fundamental role of entropy in thermodynamics. Any process that exceeds the Carnot efficiency implies a spontaneous reduction in entropy, which is forbidden by the Second Law. In reality, all practical heat engines incorporate some irreversibility (such as friction, turbulence, or non-quasistatic processes) which further reduces their efficiency below the ideal Carnot limit.

Case 4: Heat Pump Efficiency Below Carnot¶

Finally, lets consider the case where and . This will give net heat flows of:

This also violates the Second Law, as heat flows from the cold reservoir to the hot reservoir. This proves that the Carnot efficiency is maximum possible for all heat engines. It also represents the minimum efficient (or maximum coefficient of performance COP) of a heat pump.

Universality of Carnot’s Theorem¶

Although Carnot’s theorem was originally derived for gas expansion and compression cycles, its implications extend to any system that extracts work from a temperature gradient. The key principle is that no process converting heat into work can surpass the Carnot efficiency.

For example, thermoelectric devices operate as solid-state heat engines, directly converting a temperature gradient into electrical work. Similarly, geothermal power plants leverage the Earth’s internal heat as a thermal reservoir, using surface temperatures as a cold reservoir.

Regardless of the specific mechanism—whether gas expansion, solid-state transport, or fluid cycles, the Carnot theorem sets a fundamental upper bound on efficiency. Any system claiming to exceed this limit would violate the Second Law of Thermodynamics and constitute a perpetual motion machine.

Geothermal Power Efficiency¶

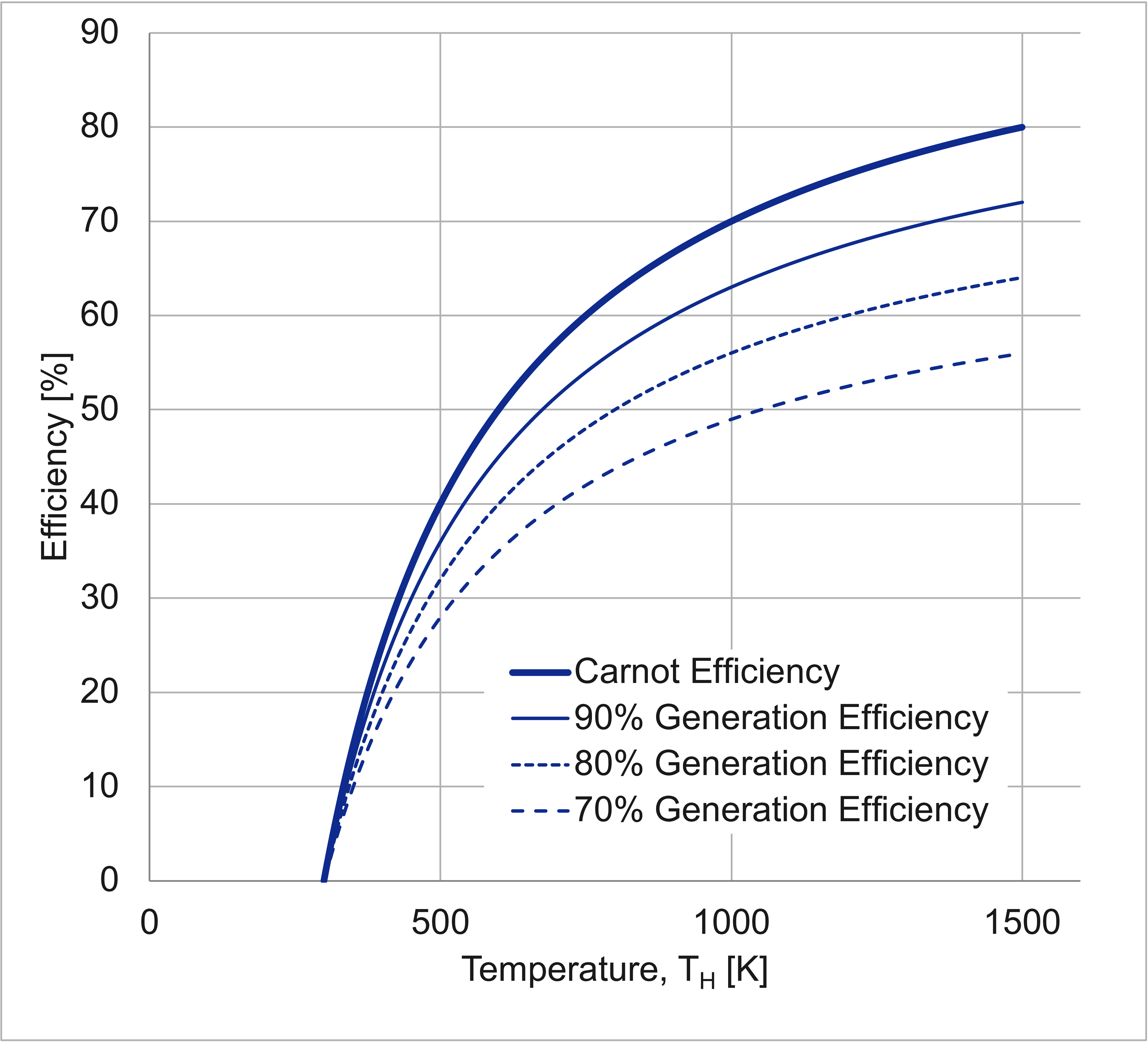

Figure 3.1.7 and Equation (3.1.13) showed that the efficiency of a Carnot engine increases with increasing for a given . However, geothermal plants in the real world experience additional efficiency losses. One of the largest losses is parasitic load, i.e. the energy required to run pumps that circulate water and steam. Many plants have parasitic loads of 20–30%, reducing their overall efficiency. Figure 3.2.2 shows the effect of these losses on the overall efficiency.

Figure 3.2.2:The efficiency of a geothermal plant operating at different temperatures and electricity generation efficiencies, accounting for the energy required to run pumps and other required steps.

The overall efficiency of a geothermal power plant is given by the product of the efficiency for heat-to-work conversion and the electrical generation efficiency.

For super-hot-rock geothermal, higher temperatures and reduced parasitic losses nearly double plant efficiency. If parasitic loads were eliminated, efficiency could approach the Carnot limit.

In the next section, we will examine phase transitions - specifically how boiling water into steam is essential for running a heat engine. Understanding these transitions is key to designing efficient geothermal systems.