Chemical Work

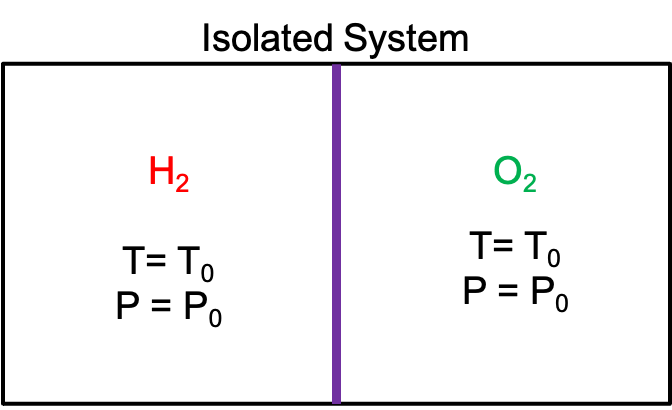

From Equation 1.2.5, we know that the mechnical work is defined as . However, this is not the only type of work available. Let us consider a thought experiment, as shown in Figure 2.2.1. The hydrogen and oxygen gases (both assumed to be ideal gas) are put inside an isolated container (impermeable to the exchange of energy and matter), and the two gases are separated by a barrier (highlighted in purple) that is impermeable to the exchange of matter. Both sides are at the same temperature () and pressure (). Let’s now break the barrier. Intuitively, we would suppose the following chemical reaction to happen

We highlight 3 points here:

- The total number of hydrogen and oxygen atoms remains fixed, as a result of the outer container wall (shown in black color) is impermeable to exchange of mass.

- Two moles of hydrogen gas react with one mole oxygen gas to form one mole of water. The chemical bonds rearrange while conserving the total number of atoms, not the number of molecules.

- If we assume this reaction to be spontaneous (a one-sided reaction where the precursors automatically combine to yield the product without added energy or being influenced by any “external factor”), it is necessarily exothermic (heat is released) and therefore we expect the temperature inside the container to increase.

Figure 2.2.1:Thought experiment to demonstrate different types of work

As defined in Table 1.2.1, for an isolated system, neither exchange of energy (heat and work) nor matter is allowed with the surroundings. Thus, we know , and with the First Law we can conclude . Since there is no change in the internal energy, there should be no change in the temperature if we assume the gases behave ideally. This contradicts Point 3 since an exothermic reaction would release heat, raising the temperature inside the container. However, since the First Law must be observed (i.e., temperature should increase), our previous definition of work () is incomplete, and we are missing other contributions to .

If we look at Point 2, we can see that so far we have not explicitly considered the effect of chemical bond rearrangement (i.e., the energy transfer that comes with breaking and form chemical bond). This missing contribution is related to such energy transfer called chemical work.

Just like mechanical work that can be converted into internal energy to increase the temperature (e.g., compressing piston to increase the air temperature inside), chemical work can also increase the temperature of a system since temperature is a measurement of the average kinetic energy of the atoms inside such system. Like and , the chemical potential is independent of the quantity of the materials. It depends upon the potential energy stored within chemical bonds, as well as bond configuration within the system. We will introduce a more rigorous definition of the chemical potential later on.

For now, the chemical potential defined in Equation 2.2.2 is only concerned with a single chemical species. For our example system, we have 3 different species: the hydrogen gas, the oxygen gas, and water. For a more complete description of all types of possible chemical work conversions, we can sum the chemical work for the species of the system as in Equation 2.2.3

By incorporating both mechanical and chemical work, we can write an expanded First Law of thermodynamics for a reversible system (i.e., where ) in Equation 2.2.4

The corresponding differential form is

In summary, Equation 2.2.5 says for a reversible change in the internal energy of the system, the first term is the heat added to or removed from the system; the second term is the mechanical work done on or by the system; the third term is the chemical energy transferred in or out of the system via the rearrangement of bonds and/or the exchange of mass.

Remember that is a state function, so since the internal energy only depends on the initial and final state of the process, not the path taken (whether irreversible or reversible). It is worth emphasizing that in the irreversible case, we can neither conclude nor . However, we can always find a reversible process with the same initial and final states as the irreversible process such that , but each individual term in the reversible equation does not necessarily needs to be equal to its counterpart in the irreversible equation. As a result, there is no reason to explicitly differentiate between irreversible and reversible processes when it comes to change in the internal energy.