The First Law of Thermodynamics

Energy can be transferred into and out of a thermodynamic system in two ways:

- Work

- Heat

Work¶

Work is one of the fundamental ways energy can be transferred between a thermodynamic system and its surroundings. In this section, we define and explore the concept of work in thermodynamics, derive key equations, and illustrate examples to build intuition.

In thermodynamics, work is the transfer of energy that occurs when a system exerts a force or causes a displacement in its surroundings. Work does not always require directed motion in the classical sense; for instance, electromagnetic fields can perform work by altering potential energies or charges. In this section however we will focus on work due to directed motion.

If you have taken a mechanics course, you may recall the definition of work as

where is the force required to move an object, and is the displacement of the object. In this definition, force is a scalar and constant. We will generalize this expression to be

For a system like a gas in a piston, the force exerted by the gas is related to its pressure and the area of the piston by:

The displacement of the piston, , results in a volume change , where:

Substituting these relationships into the definition of work:

This integral form is widely used in thermodynamics to calculate the work done by or on a system.

In thermodynamics, the sign of work depends on the direction of energy transfer:

- Positive work: Work is done by the system on the surroundings (e.g., gas expansion).

- Negative work: Work is done on the system by the surroundings (e.g., gas compression).

Example: Isothermal Expansion

Consider a gas in a piston undergoing isothermal expansion which changes the volume from to , where the temperature remains constant. From the Ideal Gas Law:

where is the number of moles of gas, is the universal gas constant, and is the absolute temperature. Substituting this into the work equation:

After integration:

This result shows that the work done in an isothermal process depends logarithmically on the ratio of final to initial volumes.

Heat¶

The second fundamental way energy can be transferred between a thermodynamic system and its surroundings is heat . In this and the following section, we define and explore the concept of heat in thermodynamics, derive key equations, and illustrate examples to build intuition.

Heating is the transfer of energy caused by random molecular motion. Unlike work, which involves organized motion in a specific direction, such as a piston moving upward, heat is associated with disorganized, random motion of molecules. For example, when heat is added to a system, the random velocities of the gas molecules increase, raising their average kinetic energy. The sign of heat is positive when energy is added to the system and negative when energy leaves the system.

Heat Transfer¶

If you have taken an introductory physics course, you may recall that heat transfer is often expressed as:

where is the mass of the material, is its specific heat capacity in units of J/(kg·K), and is the change in temperature. This equation describes the amount of heat required to change the temperature of a material.

In systems where the quantity of the material is more conveniently expressed in moles, we can rewrite this equation in terms of the number of moles and the molar heat capacity (at constant pressure) in units of J/(mol·K):

In this section, we will generalize these expressions to account for heat transfer in a variety of systems and conditions.

Heat transfer occurs via four main mechanisms:

- Conduction - Transfer of heat through a solid or stationary fluid due to molecular interactions.

- Advection - Transfer of heat through the bulk motion of a moving fluid.

- Convection - Combined heat transfer by conduction and advection in a fluid.

- Radiation - Transfer of heat via electromagnetic waves without requiring a medium.

We typically describe heat transfer using the heat transfer rate , equal to

where is the change in heat, and is the time interval.

Conduction¶

Energy transfer through direct contact between molecules is known as conduction, and is governed by Fourier’s law:

where is the thermal conductivity, is the cross-sectional area, and is the temperature gradient or temperature difference over some distance .

Advection¶

Advection refers to energy transfer due to the bulk motion of a fluid, governed by the equation:

where ρ is the fluid density, is the specific heat capacity of the fluid at constant pressure, is the velocity vector of the fluid, is the area through which the fluid flows, and is the temperature difference in the fluid.

Advection is particularly important in processes involving strong bulk fluid flow, such as heat transport in pipelines, molten metal casting, or atmospheric heat distribution.

Convection¶

Energy transfer through fluid motion is known as convection, which involves both conduction and advection. We can express it as:

where is the convective heat transfer coefficient, is the area through which the fluid flows, and is the temperature difference.

Radiation¶

Energy transfer via electromagnetic waves is known as radiation, and is governed by the Stefan-Boltzmann law:

where σ is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, is the area, ε is the emissivity of the surface, is the temperature of the object, and is the temperature of the surroundings.

Heat vs Work¶

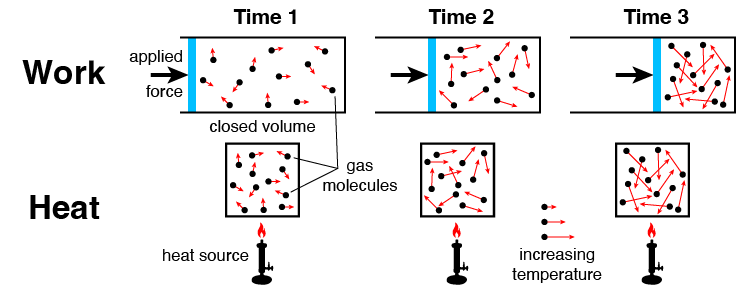

The distinction between heat and work lies in the nature of the motion. In work, molecules move collectively in a coordinated direction to transfer energy. In heat, energy transfer occurs through random motion in all directions. Both heat and work involve energy transfer, but they do so in fundamentally different ways. Figure 1.2.1 illustrates this distinction by showing how work and heat manifest through the motions of gas molecules.

Figure 1.2.1:Increasing gas temperature via work or heat. By time 3, the states are indistinguishable, meaning that we cannot determine if the increased temperature is due to heat transfer or applied work.

When we apply a force to the piston in Figure 1.2.1, energy is transferred from the motion of the piston moving to the right, into increased motion of the gas molecules from collisions with the wall. In contrast, adding heat directly to the enclosed volume in Figure 1.2.1 increases the random velocities of gas molecules by raising their kinetic energy.

Internal Energy and the First Law of Thermodynamics¶

The internal energy of a system, denoted , is the total energy contained within the system. This includes all forms of microscopic energy, such as the kinetic energy of molecular motion and the potential energy of molecular interactions. Internal energy is a state function, meaning its value depends only on the current state of the system and not on the path taken to reach that state.

The first law of thermodynamics expresses the conservation of energy in a thermodynamic system. Equation (1.2.16) reflects the balance of energy within the system. Each term represents a different mode of energy transfer which we discussed above:

- : Heat added to the system increases the internal energy.

- : Work done by the system decreases the internal energy.

Thermodynamic Sign Convention¶

In thermodynamics, defining the 1st law as leads to the following sign convention:

- () Heat added to the system is positive.

- () Heat leaving the system is negative.

- () Work is done by the system (onto its surroundings).

- () Work done to the system (by its surroundings).

With this sign convention, applying positive pressure () to reduce the volume of a system, we calculate the work to be . This results in a negative value for work (), indicating that work is done on the system, increasing its internal energy .

Chemistry Sign Convention¶

In this context, the 1st law is defined as , leading to the following sign convention:"

- () Heat added to the system is positive.

- () Heat leaving the system is negative.

- () Work is done by the system (onto its surroundings).

- () Work done to the system (by its surroundings).

With this sign convention, when we apply positive pressure () to reduce the volume of a system, we calculate the work to be . This results in a positive value for work (), indicating that work is done on the system, increasing its internal energy .

Choosing a Convention¶

Why the difference? The choice of sign convention reflects whether the focus is on the system or its surroundings:

- Thermodynamics Convention: Widely used in physics and engineering, emphasizes energy flow and interactions with surroundings.

- Chemistry Convention: Focuses on the system itself, often aligning with experimental measurements like pressure-volume work.

In this course, we will use the sign convention defined above in Equation (1.2.16). This convention is most often found in thermodynamic and engineering situations. One way to ensure that your calculations are always self-consistent is to remember that both must reduce to this form:

Thermodynamic Systems¶

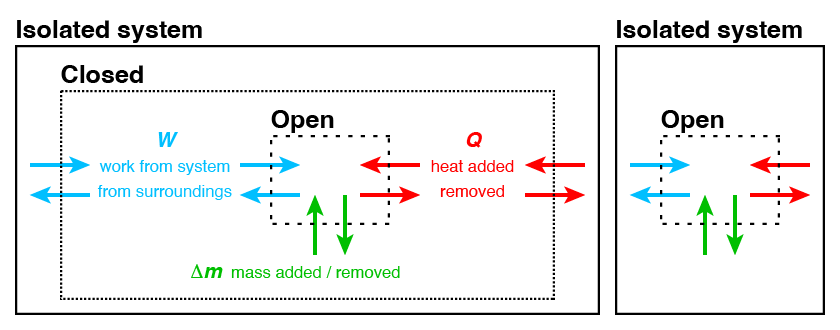

We can classify thermodynamic systems into 3 categories based on their interface conditions, summarized in Table 1.2.1 and illustrated in Figure 1.2.2:

- An open system allows heat, work, and mass to cross its boundaries.

- A closed system permits only heat and work transfer, while mass remains contained.

- An isolated system allows no exchange of heat, work, or mass with its surroundings.

Table 1.2.1:Classification of thermodynamic systems by boundary conditions.

| System Type | Permeable to Heat and Work | Permeable to Matter |

|---|---|---|

| open | yes | yes |

| closed | yes | no |

| isolated | no | no |

Figure 1.2.2:(left) An isolated thermodynamic system which contains a closed system, which itself contains an open system. (right) An isolated system which contains an open system.

Consider the closed system contained inside the isolated system in Figure 1.2.2. The first law of thermodynamics states

where and refer to heat transferred across the boundary, and and refers to work done by the system on the surroundings and vice versa. The total amount of energy in the closed system changes by exactly the amount of heat added/removed to the system and the work done by/to the system, i.e. total energy is conserved.

By definition, an isolated system has , and therefore remains constant.

We can also categorize thermodynamic systems or processes into 4 categories based on the constraints imposed on state variables:

- Isothermal - The system undergoes a process at constant temperature . Heat transfer occurs to maintain thermal equilibrium as work is done or energy changes.

- Isobaric - The system experiences a process at constant pressure . Heat transfer can lead to changes in volume and temperature.

- Isochoric - The system’s volume remains constant. No work is done, and any energy transfer appears as heat.

- Adiabatic - The system is thermally insulated, so no heat is exchanged (). Changes in the system’s energy result entirely from work done on or by the system.