Voltage of a Fuel Cell

Standard Chemical Potential¶

Equation 2.5.2 shows that the chemical potential difference between reactants and products in the fuel cell overall reaction leads to a difference in the electron chemical potential in the cathode and the anode. Such an electron chemical potential difference can be measured with a voltmeter as the open-circuit voltage ,

where is Faraday’s constant and ( is Coulomb; μ can be in units of or ). The negative sign is a result of the electrons being negatively charged. Thus, an electric potential higher in magnitude means an electron under the influence of such potential will have more negative electron energy. With Equation 2.6.1 and Equation 2.5.2 combined, we obtain the open-circuit voltage for our fuel cell,

The voltage (also known as the Nernst potential) is a direct measure of the difference in chemical potentials for the species involved in the overall fuel cell reaction. As mentioned before, the fuel cell develops a precise voltage difference between the cathode and the anode to balance out the chemical potential difference between the reactants and the product in the two electrodes, such that the equilibrium is achieved in the anode, cathode and the electrolyte/membrane as seen in Table 2.5.1.

We now want to relate the difference in chemical potential and the open-circuit voltage to the partial pressure of each species in the overall fuel cell reaction. Recall from Equation 2.5.6 that the chemical potential of species is the difference between its partial molar enthalpy () and the product between the temperature and its partial molar entropy ():

As the reaction proceeds, consider how this chemical potential would change: the partial molar enthalpy represents the chemical energy stored in each bond of species , which does not change with the extent of the reaction; the partial molar entropy represents the infinitesimal change in the configurational entropy with an infinitesimal amount change in the number of moles of species , which would change as the species is consumed or produced. Thus, throughout the course of the reaction, would remain fixed, but would change with varying concentrations of species . From Equation 1.4.8, we learned that for an ideal gas, its entropy depends on the pressure of the gas. Modified for a system with multiple ideal gas species, we can write the total entropy as

where is the entropic contribution from species to the total entropy, is the number of moles of species , and is its partial pressure (; is the total pressure here). The simple summation over every species is made possible by the fact that gas molecules do not interact with one another for ideal gases. Using the definition of partial molar quantities, we have

Note that the summation sign over in Equation 2.6.3 disappears when we take the partial derivative with respect to . This is due to fact that we are holding constant, where only one term within the summation will have dependence. Furthermore, when is held constant, what we really mean is that the total pressure is held constant. Some of you may wonder how can the total pressure be held constant when is allowed to vary but all other terms are held constant. One way to maintain the total pressure is as increases or decreases, we allow the total volume of the system to increase or decrease accordingly. For Equation 2.6.4, when the species is in the dilute limit (i.e., , thus ), we can make an additional approximation where . Strictly speaking, the argument of a natural logarithm should be unitless. We can resolve this issue by expressing as some initial measured at some reference pressure and adding to it the difference in partial molar entropy measured between the reference pressure and the actual partial pressure. Mathematically, this is shown as follows,

Here, is the standard pressure such that when . For this class, we typically choose 1 atm or 1 bar as in the problem sets and exams. Combining Equation 2.5.6 with Equation 2.6.5, we then have

An extra note on : it does not only account for the configurational partial molar entropy at the standard state, but also accounts for all other sources of entropy, such as the vibrational, rotational and electronic partial molar entropy. Now, we can also combine the first two terms in Equation 2.6.6 into a single term that we will call the standard chemical potential of species , which we will denote as . This allows us to separate the chemical potential into two parts, with one part being independent of the partial pressure and the other being dependent on the partial pressure.

Since all partial molar quantities are defined at constant temperature and pressure, the standard chemical potential is usually defined at room temperature and room pressure (i.e., and 1 atm). The reason for defining such standard chemical potential is that, with a standard state, one can measure and tabulate the chemical potentials of many common chemical species. Since measuring partial pressure differences is much easier than directly measuring a new chemical potential, when the partial pressure of the species deviates from the reference pressure, one can simply calculate the new chemical potential using Equation 2.6.7 by looking up the tabulated standard chemical potentials and accounting for the partial pressure difference.

Going back to the open-circuit voltage, we can express all the chemical potentials in the same form as Equation 2.6.7,

Collecting all like-terms, we obtain partital pressure dependent open-circuit voltage

The first three terms within the square bracket define the (inverse) standard chemical potential of the reaction,

The standard reaction chemical potential is the change in the Gibbs free energy of the system per mole of the extent of the reaction when the reactants and the products all have their partial pressure equal to . The last term describe the configurational-entropic contribution to the change in the standard reaction chemical potential. Not suprisingly, Equation 2.6.8 states that the open-circuit voltage of the fuel cell not only depends on the types of reactants and products, but also on the concentration/partial pressure of each species.

A Note on Units¶

In Equation 2.6.8, since is defined as Coulomb per mole of electrons, the open-circuit voltage in that equation are in units of volt per mole of electrons. That being said, it is equally valid to define voltage in terms of volt per single electron, and with proper conversion factors, Equation 2.6.8 becomes

Here, is the chemical potential of a single molecule/atom of a species in units of electron-volts (), rather than the chemical potential of a mole of the species with units of . An electron-volt if the potential energy of an electron across the voltage of 1 . The charge of a single electron is as seen in Equation 2.6.10, which is equal to . In summary, all the constants in Equation 2.6.10 differ from those in Equation 2.6.8 by Avogadro’s number , where , , and in Equation 2.6.8 is equal to multiplied by in Equation 2.6.10.

For this course, we will mostly use , and in units of per mole. These units are more typical of chemistry. More physics-oriented courses tend to use , , and in units of per electron/molecule. You are welcome to use whatever units you feel more comfortable, and sometimes there are scenarios when one convention leads to numbers that are easier to work with than those under the other convention. Make sure you don’t mix up the units in a single equation. If you mix them up, you may get unphysical quantities on the order of for the open-circuit voltage. If you do find yourself getting such values, check that you are using consistent units.

Dependence of Voltage on Partial Pressure¶

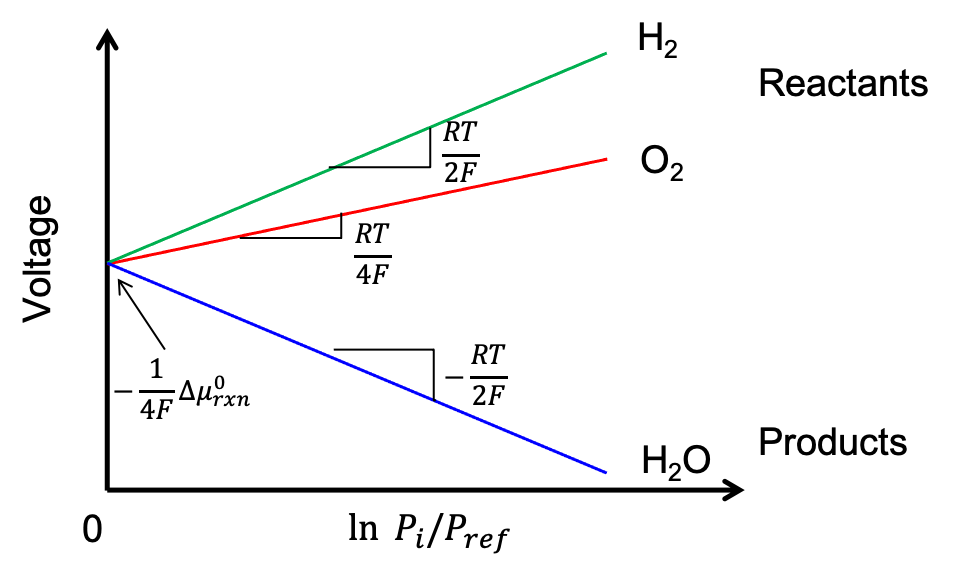

To gain a deeper understanding of the open-circuit voltage’s dependence on partial pressure, we plot the voltage as a function of the natural log of partial pressure of each species in Figure 2.6.1. Here, only one component’s partial pressure is varied at a time. When , the fuel cell’s voltage is only given by the standard reaction chemical potential (this is shown as the same voltage-axis intercept for all three chemical species in Figure 2.6.1). We can see that the voltage increases when the partial pressure of oxygen or hydrogen gases increases; the voltage decreases when the partial pressure of water increases.

Figure 2.6.1:The voltage of a fuel cell as a function of the natural log of partial pressures. The intercept is determined by and can be changed by modifying the chemistry of the reaction. Increasing the reactant concentrtion increases the voltage, while increasing the product concentration decreases it.

To make sense of why the voltage increases with increasing oxygen or hydrogen partial pressures but decreases with increasing water partial pressure, let’s revisit the net fuel cell reaction where hydrogen and oxygen react to form water, . Let us imagine a fuel cell with lots of water and very little hydrogen and oxygen gases (i.e., high , low and low ). In such a fuel cell, there is almost no driving force to produce more water. Accordingly, this fuel cell has a small voltage since there is no driving force for hydrogen and oxygen to react to form more water. Alternatively, if a fuel cell has lots of hydrogen and oxygen gases but very little water (i.e., low , high and high ), there will be a significant driving force for hydrogen and oxygen gases to react to form water, leading to a high voltage. Such trends for voltage vs. partial pressure of reactants and product are consistent with the voltage lines plotted in Figure 2.6.1.

Voltages with Different Fuels¶

The voltage of a fuel cell depends on the type of the chemical species involved. So far, we have only considered hydrogen and oxygen gases as reactants and water as the product. From Equation 2.6.9, with tabulated values at the standard condition, we can calculate the standard reaction chemical potential to be of consumed. Thus, at and .

Now let’s change the mobile ion from the oxygen ions () to the protons (). In such a fuel cell, the reactions become:

Since the total number of electrons transferred and the overall reaction are the same as the fuel cell with as the mobile ions, this alternative fuel cell with ions has the same open-circuit voltage expression as that in Equation 2.6.8. Such equivalence is underpinned by an important concept in thermodynamics: the Gibbs free energy and subsequently the open-circuit voltage are two thermodynamic variables that are state variables. That is to say these two variables are independent of the path taken in-between the initial and final states. Here, regardless of the mobile carrier being oxygen or hydrogen ions, the change in the molar Gibbs free energy is the same since the initial and final states in both overall reactions are the same, with the initial state being 2 moles of , 1 mole of and the final state being 2 moles of . Thus, the open-circuit voltage of a fuel cell based on proton conduction is equal to that of one based on oxygen ion conduction.

Finally, let’s change the hydrogen gas to methane. If oxygen ions can traverse through the membrane, the chemical reactions become:

Here, at , and . This voltage differs from the hydrogen-oxygen fuel cell because the replacement of hydrogen with methane changes the bond energy difference upon reaction of methane and oxygen into water and carbon dioxide, which leads to a significant difference in the initial and final states of the overall reaction. In a nutshell, while changing the mobile ions in fuel cells while keeping the initial and final states the same in the overall reaction does not change the open-circuit voltage, changing the types of chemical species can.