Minimum Work for Separating CO₂

Minimum Work for a Reversible Process¶

To calculate the minimum work required to separate and capture carbon dioxide, we begin by considering the thermodynamic principles governing the process. For a closed, isothermal system, the First Law of Thermodynamics gives:

where is the heat transferred, is the work done, and is the change in internal energy. Combining this with the Second Law of Thermodynamics:

yields:

The lower bound of this inequality represents the minimum work , which corresponds to a reversible process.

Mixing and Demixing¶

Consider the system depicted in Figure 1.1.4, where a partition separates carbon dioxide (CO2) and another gas. When the wall is removed, the gases mix, increasing the entropy of the system. Conversely, demixing (or separating the gases) requires work to decrease the entropy. Because mixing and demixing are opposite processes, their associated entropy changes are equal in magnitude but opposite in sign:

The minimum work for demixing is therefore given by:

This work represents the energy required to carry out the process reversibly.

Entropy of Gas Expansion¶

Derivation from Microstates¶

When gases mix, their individual volumes expand, increasing their entropy. To calculate the entropy of mixing, we define the following parameters:

- α: Volume fraction of CO2.

- : Total moles of gas.

- : Total volume of gas.

From Equations (1.1.20) and (1.1.22), we can write

where is the total number of molecules, is the Boltzmann constant, is the number of moles, and is the gas constant. We know that is proportional to and number of lattice sites is proportional to volume . Therefore, we can rewrite Equation (1.3.19) to be

where the added constant represents the proportionality constant inside the natural logarithm term.

We can see from Equation (1.4.7) that as the volume expands at constant and , the entropy increases. This occurs because a larger volume provides more lattice sites, reducing the fraction of occupied sites and thus increasing the disorder of the gas. Another way to understand this expansion is to use the ideal gas law, Equation (1.1.23), and the assumption of constant temperature to get

This expression shows that as the pressure decreases, the entropy if the system will increase. If we evaluate the change in entropy if the pressure changes from to , we get

Derivation from Thermodynamic Principles¶

We can also derive Equations (1.4.8) and (1.4.9) without needing to rely on the counting the microstates of the system. Starting from the First Law, we know that . In a closed isothermal system we know that , and therefore . Recall that for a reversible process:

where is the total pressure of the system. From these relations we can derive that

From the ideal gas Equation (1.1.23) we know that , and therefore (when and are constant)

Combining these equations and evaluating the integral we get

which is the same result as given in Equation (1.4.9). Both approaches show that the change in entropy scales with .

Previously, we derived the same entropy expression based on partial pressure using a statistical approach. In this second approach, we derived the relation for a reversible, isothermal gas expansion using the ideal gas law and the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Why are these methods equivalent? The ideal gas law is rooted in the statistical mechanics of microstates, so while the derivations appear different, they ultimately reflect the same underlying principles.

Entropy of Mixing¶

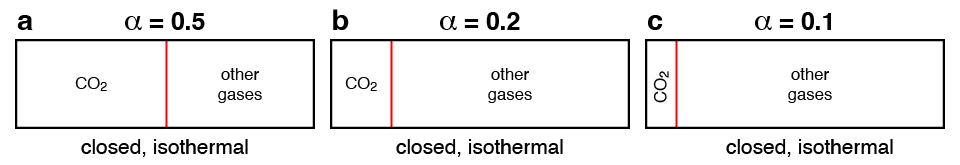

Figure 1.4.1 shows a closed isothermal system, where the left chamber contains a volume fraction α of equal to

where and are the volumes of the CO₂-containing portion and the total system respectively. We will assume both compositions are ideal gases, and thus the volumes vary linearly with the number of moles of each substance. We can therefore define α as the number fraction, equal to

where and are the number of moles of the CO₂-containing portion and the total system respectively.

Figure 1.4.1:Three boxes partitioned into two chambers under identical pressure , consisting of varying fractions α moles of CO₂ and () moles of another gas.

Let’s consider what happens when we remove the partition as a function of α for the 3 scenarios in Figure 1.4.1:

- a) Both gases double in volume.

- b) CO2 expands to its volume, and the other gases to their original volume.

- c) CO2 expands to its volume, and the other gases to their original volume.

We see that the volume expansion of each side depends on the fraction α. Specifically, the ratio of the initial volume to the final volume for CO₂ is equal to

and the volume ratio for the other gases is equal to

Next, let’s consider the entropy of mixing before and after mixing

From the ideal gas law given in Equation (1.1.23) we know that pressure and volume are inversely proportional when and are kept constant. We can therefore rewrite Equation (1.4.9) to be

We can plug in the volume ratios given above to compute the total change in entropy

Whenever deriving a new mathematical relationship, we should always ask ourselves if the result is sensible. Let’s consider the edge cases for α, specifically when and . In both of these cases, both logarithmic terms in Equation (1.4.20) will go to zero and thus . This makes sense, as if there is no partition, removing it cannot change the entropy of the system.

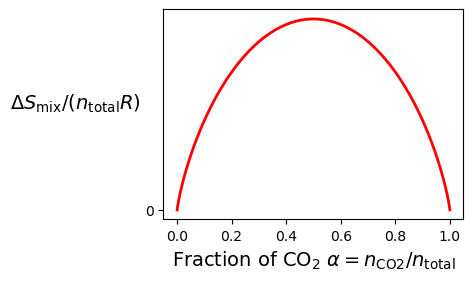

Next, we examine the values of for values , plotted in Figure 1.4.2. We can see that the entropy of mixing has mirror symmetry about the line, which makes sense because both sides of the chamber contain ideal gases at the same pressure value.

Figure 1.4.2:Entropy of mixing for CO₂ and the other gases.

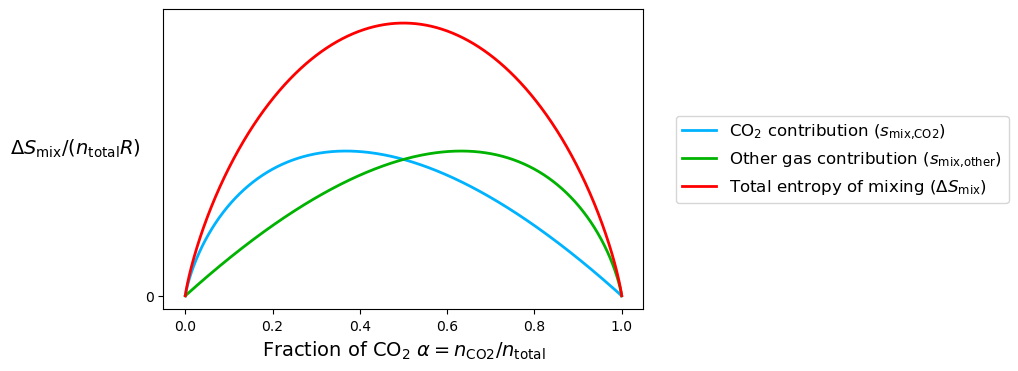

The entropy of mixing has mirror symmetry about , which makes sense because both sides of the chamber contain ideal gases at the same pressure. At , the two gases are present in equal amounts, with half CO₂ and half of the other gas. This creates the maximum disorder because each gas expands into the largest possible fraction of the total volume. But why doesn’t (or ) result in more entropy of mixing, since one gas occupies 75% of the volume? The answer lies in how both gases contribute to the entropy, shown explicitly in Figure 1.4.3.

At , CO₂ occupies 25% of the total volume, so it contributes less to the entropy compared to , where CO₂ occupies 50%. Meanwhile, the other gas, which occupies 75% of the volume at , has fewer ways to mix compared to , where it also occupies 50%. The key point is that both gases contribute to the entropy of mixing, and the total entropy is maximized when the contributions from both gases are balanced, which happens when .

To understand this intuitively, imagine mixing red and blue balls in a box. When you have an equal number of red and blue balls, there are far more ways to arrange them compared to when one color dominates. This balance maximizes the number of possible arrangements (microstates), which corresponds to the maximum entropy of mixing at .

Figure 1.4.3:Entropy of mixing for CO₂ and the other gases, with individual contributions from each shown.

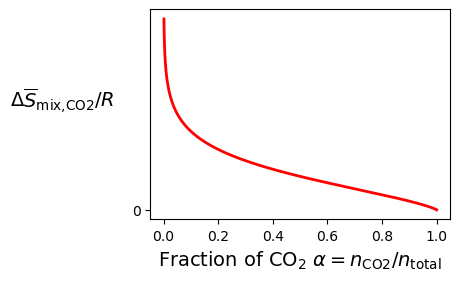

So far, we have only considered the total entropy of mixing. However, for the CO₂ separation application, instead we need to consider the entropy of mixing normalized by how much CO₂ we separate from other gases. This normalization will make it much easier to compare CO₂ separation between different applications, such as those shown in Figure 1.1.3.

We therefore need to calculate the minimum work required to separate CO₂ per mole of CO₂. If we assume this work is dominated by the entropy of mixing, this value will be the result of Equation (1.4.20) divided by the number of moles of CO₂, equal to

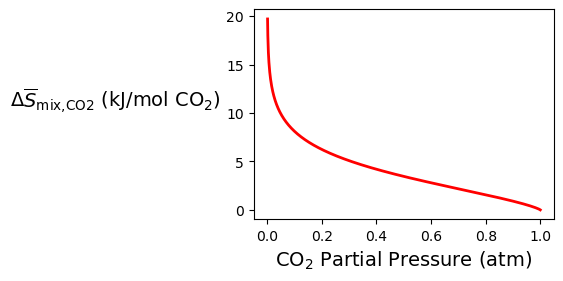

This expression is plotted in Figure 1.4.4, which as we can see matches the result shown in Figure 1.1.3 up to a numerical scaling factor. We can identify several key features from this model:

- As , the work required to separate each mole of CO₂ approaches infinity. This intuitively makes sense, as gathering extremely small amounts of a dilute gas would require a lot of sorting target molecules from all of the others.

- As , the work required to separate each mole of CO₂ approaches zeros. This also intuitively makes sense, as at we already have a volume of pure CO₂ and thus do not need to perform the any further separation.

- As α increases, the work required to separate each mole of CO₂ decreases.

- Beyond , the work required decreases approximately linearly.

Figure 1.4.4:Specific entropy of mixing for CO₂.

Minimum Work for Gas Separation¶

To conclude, we now have all of the pieces required to quantitatively compute the thermodynamic minimum work required to separate CO₂, as a function of the number of moles of CO₂ and temperature. Knowing that and referring to Equations (1.4.5) and (1.4.20), we can write

We can perform the same normalization as in Equation (1.4.21) to calculate the specific work requited to separate one mole of CO₂ to be

The units of are J / mole CO₂. We can again see that separating a mole of CO₂ from a source with low CO₂ concentration will require more work than separating CO₂ from a source containing a high CO₂ concentration. As shown in Figure 1.1.3, capturing CO₂ from flue gas will require less work than capturing CO₂ from the atmosphere. Equation (1.4.23) always shows that the work requited will always be negative, which matches our sign convention that we need to input work into the system for gas separation.

Typically, when working with gases we will express their quantity using partial pressures, which the pressure value of each individual gas component. In this case, the partial pressures of CO₂ and the other gases are equal to

where the total pressure . Inserting these values into Equation (1.4.23) yields

We can also use Equation (1.4.25) to calculate the minimum work to separate CO₂ with real units. The ideal gas constant is equal to 8.314 J/(K⋅mol). This minimum work is plotted in Figure 1.4.5 for one atmosphere of pressure ( atm) and room temperature ( K), equal to

Figure 1.4.5:Specific entropy of mixing for CO₂.