Fuel Cell vs. Heat Engine

At the beginning of this module, we stated that a fuel cell can be much more efficient than a heat engine. Now, we will revisit this topic by defining and calculating the efficiency of a fuel cell and that of a heat engine.

Recall that the chemical work created by reactions in a fuel cell is obtained by directing electrons to flow in the circuit, which directly converts chemical energy stored in bonds as electrical work. We define the efficiency (η) as the maximum possible (electrical) work harvested () divided by the change in the bond energy, which is just the reaction enthalpy (). At constant pressure, this efficiency is also known as the thermal efficiency .

Short proof that at constant pressure

Based on Equation 2.3.13, we can see that with constant pressure (),

Thus, we can see that at constant pressure, . This equivalence is why the efficiency at constant pressure can be called thermal efficiency.

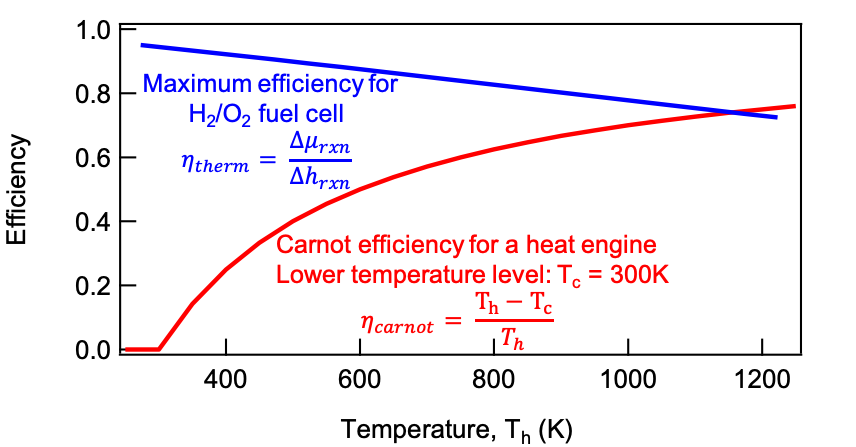

Using hydrogen and oxygen as reactants in the fuel cell, Figure 2.7.1 shows that the fuel cell efficiency is higher at low temperatures and decreases with increasing temperature. The reason that the fuel cell efficiency decreases with increasing temperature is that the overall reaction’s entropy decreases with creation of water (Intuitively, you can rationalize this as 2 moles of is created by consuming 2 moles of and 1 mole of ). The negative reaction entropy means heat is released to the environment rather than be utilized to contribute to the open-circuit voltage of the fuel cell. At higher temperatures, based on , the term’s contribution becomes more significant. With , will increase with increasing temperature.

Most importantly, remember that the formation of water is an exothermic reaction, which means , and since the chemical bond energy change should not have strong temperature dependence, it can be treated as constant when we vary temperature. As a result, even though is increasing, it is becoming less negative, and it’s magnitude decreases with increasing temperature. As a result, 's magnitude decreases with increasing temperature and thus smaller open-circuit voltage, leading to a decreasing thermal efficiency of the fuel cell. That being said, there are other types of reactants where the voltage does not fall with increasing temperature, where at least as many moles of gas are created as those that are consumed ().

Figure 2.7.1:The efficiency of a fuel cell compared to the Carnot efficiency of a heat engine.

As we will learn in the next module, the efficiency of a heat engine is defined by the Carnot efficiency:

where is the temperature of the hot heat reservoir and is the temperature of the cold heat reservoir. From Figure 2.7.1, the fuel cell efficiency is higher than that of a heat engine below , and above this temperature, the heat engine is more efficient. Notice that both the fuel cell and heat engine can’t achieve efficiency, even without heat loss or friction. There exists a fundamental thermodynamic limit where chemical/thermal energy cannot be converted into useful work (mechanical, electrical, etc.) at .