Voltage of a Battery

A battery is thermodynamically similar to a fuel cell with closed chambers. In a fuel cell, the chambers contain water and oxygen/hydrogen gases, whereas in a Li‑ion battery these gases are replaced with lithium. (Lithium does not easily exist as a gas at ambient temperature and pressure; instead it is stored as a solid or by intercalation into host compounds such as , , or graphite.)

In the fuel cell the mobile ion is (which, along with an electron and , forms ). In a Li‑ion battery the mobile ion is , which reacts with an electron and a metal oxide (e.g. ) to form . This battery chemistry is now standard for portable electronics.

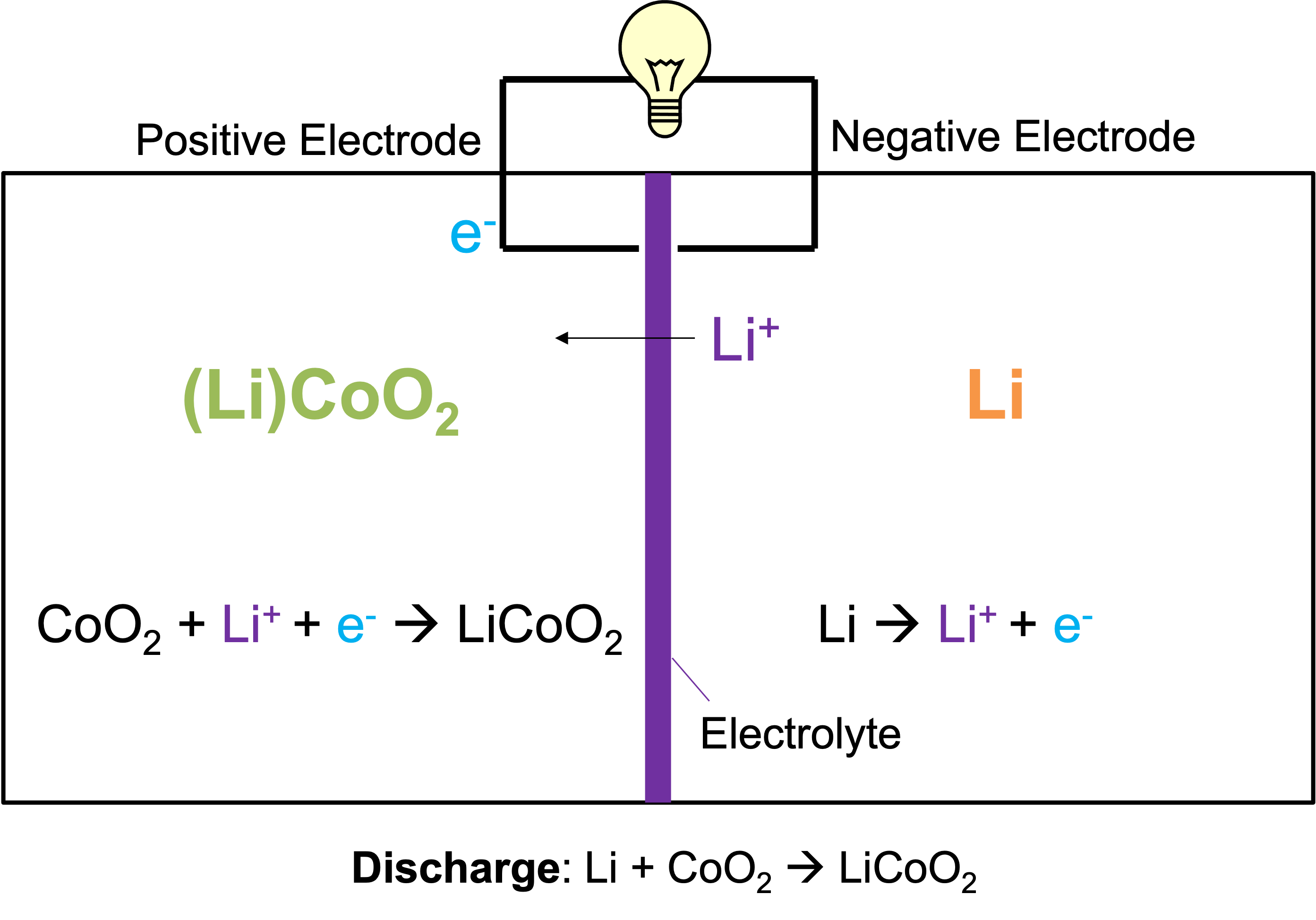

Figure 4.3.1:Schematic of a Li-ion battery under discharge.

Figure 4.3.1 schematically shows a Li‑ion battery with different host materials on the two sides (implying different chemical potentials for ). Let’s calculate the battery voltage using the same approach as in Module 2. In equilibrium, the two half‑reactions (as well as the mobile ion) must be balanced:

Since electrons cannot equilibrate between the two electrodes without shorting the battery, the net reaction is

Applying the equilibrium condition (similar to Equation 2.5.2) gives:

Here, is the chemical potential of in metallic form and is the chemical potential of when inserted in the host. For simplicity, we denote the in as “Li” and write .

Recall that the battery voltage is given by the difference in chemical potential between the negative and positive electrodes:

A positive voltage implies that the chemical potential of is higher in the negative electrode (metallic ) than in the positive electrode (where reacts with to form ). To discharge a battery, moves from a region of higher potential (negative electrode) to one of lower potential (positive electrode), producing electrical work.