Battery as a Closed Fuel Cell

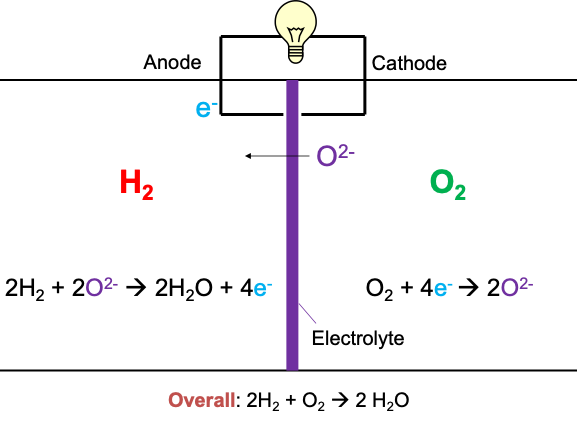

Recall that in Module 2 we examined a fuel cell schematic (see Figure 4.2.1). The voltage of the fuel cell is given by the Nernst equation:

Figure 4.2.1:Schematic of a fuel cell from Module 2

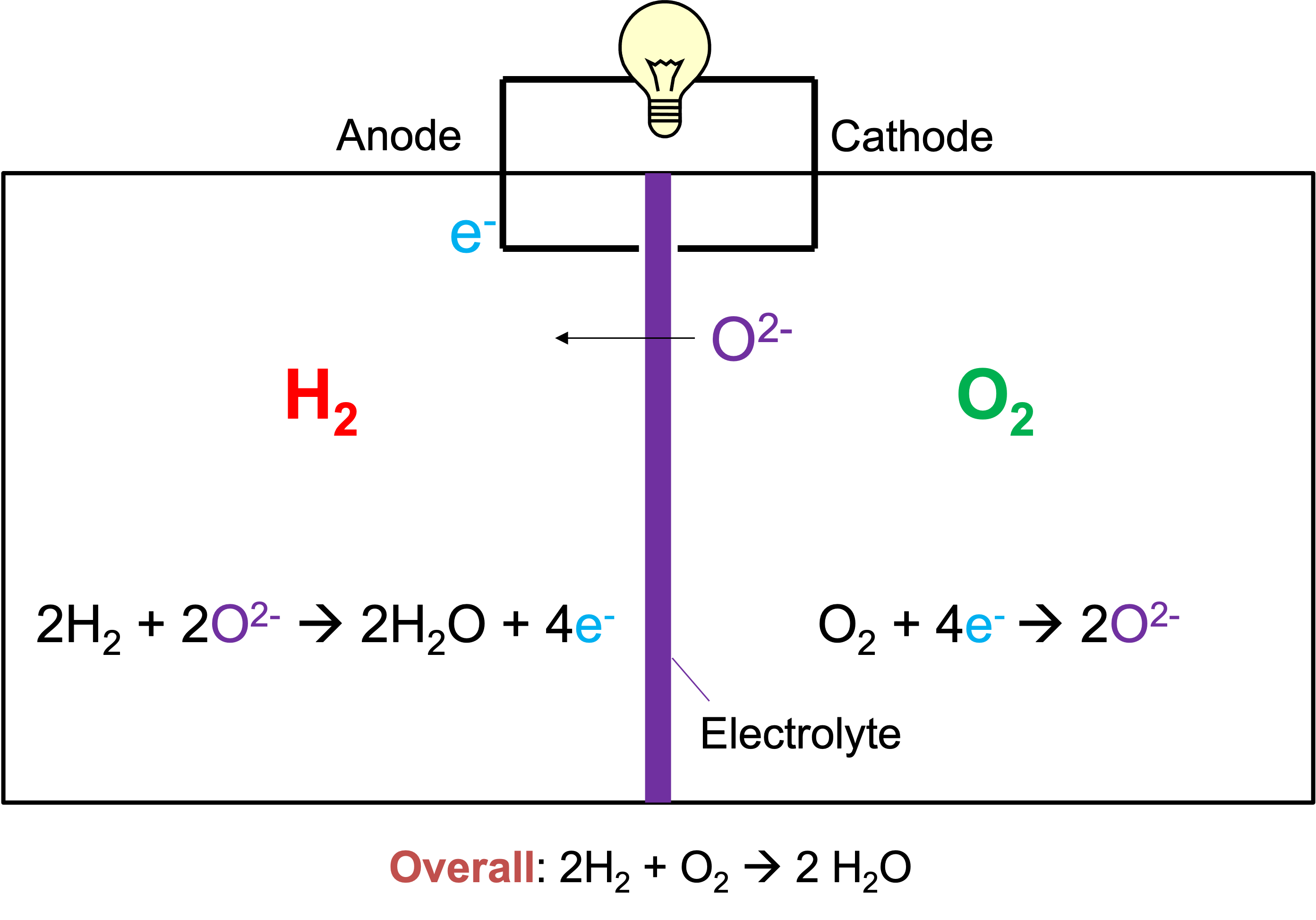

At first glance a fuel cell appears very different from a battery. Fuel cells convert chemical energy into electrical work, whereas batteries store electrical work. However, consider a modified fuel cell (see Figure 4.2.2): instead of an open system with a constant flow of oxygen and hydrogen gas to maintain partial pressures, the number of gas molecules is fixed.

Figure 4.2.2:Schematic of a closed fuel cell.

As current is drawn, the partial pressures , , and change. Suppose the initial conditions are:

Then the voltage becomes

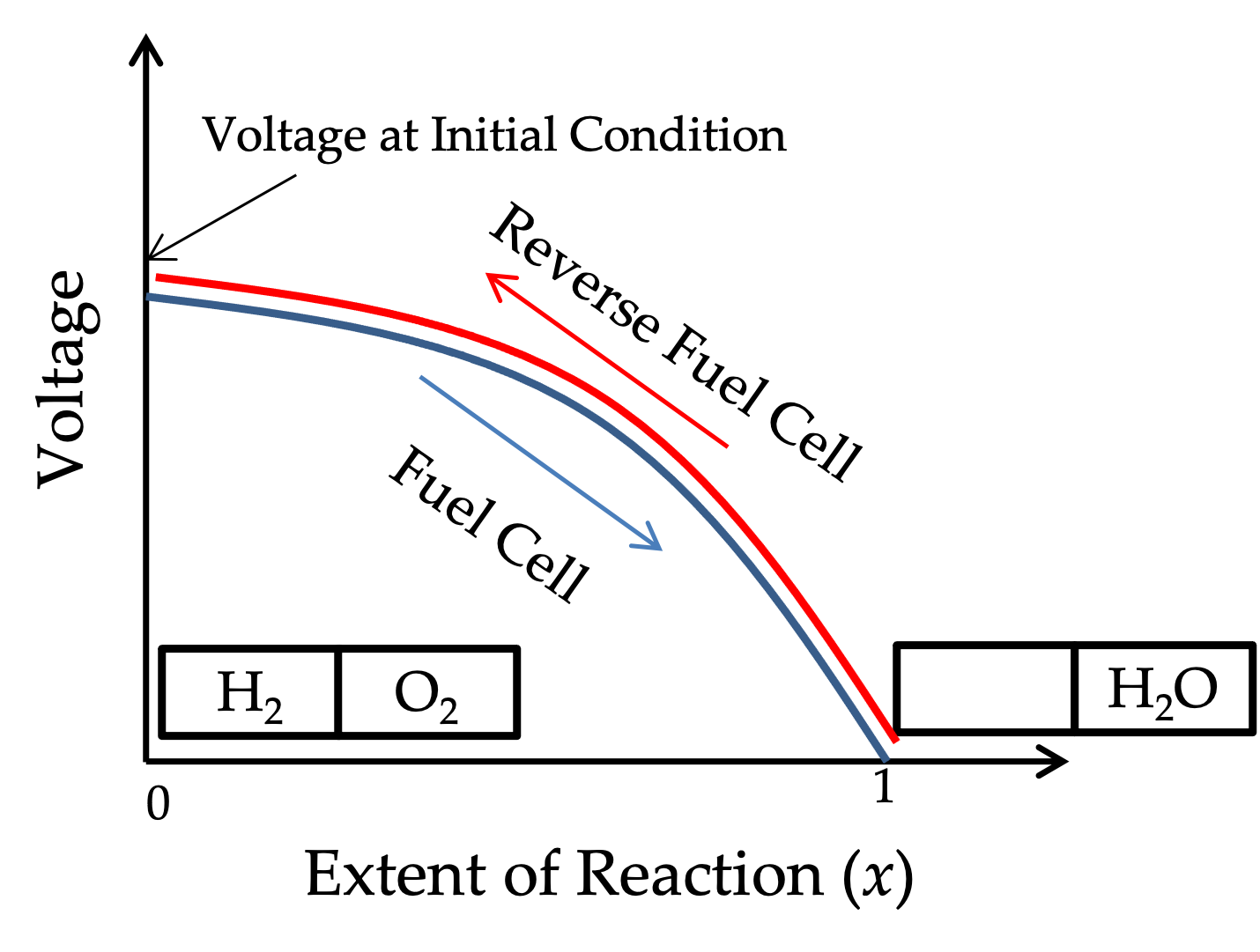

where is the fraction of molecules that have reacted (the extent of reaction) and the reference pressure has been dropped for convenience. As approaches 1, almost all hydrogen is consumed and the water partial pressure increases to . Plotting as a function of gives the curve shown in Figure 4.2.3.

Figure 4.2.3:The voltage of a closed fuel cell decreases as the hydrogen fuel is consumed.

After prolonged operation the voltage approaches 0 because almost no hydrogen fuel remains. At that point, the gases reach equilibrium and no further reaction occurs. To restore the cell, one can reverse the process—splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen by applying a voltage (electrolysis). In the quasi-static (very slow) limit, the voltages for both the fuel cell and the reverse fuel cell are identical.

Thus, in fuel cell mode the device converts chemical energy into electrical energy (discharge), and in reverse fuel cell mode (electrolysis) it converts electrical energy into chemical energy (charge). Notice that as hydrogen is consumed, the voltage changes. Later we will see that in a Li-ion battery the voltage similarly changes with the amount of Li inserted into the electrodes.